Pope John Paul II’s Encounters with Polish Jews

Stanisław Krajewski

27/03/2020 | Na stronie od 27/03/2020

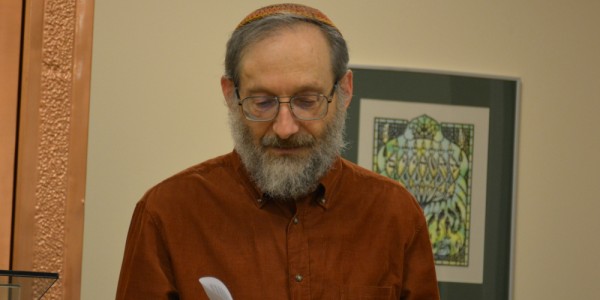

Stanisław Krajewski - professor (ordinarius) of Philosophy, University of Warsaw. PhD in mathematics, 'Habilitation' in philosophy, state conferred title professor of humanities. Chair of the Academic Council of the Institute of Philosophy, University of Warsaw. Co-chair of the Polish Council of Christians and Jews. Co-author of the core exhibition in Polin, Museum of the History of Polish Jews, in Warsaw.

SCJR 15, no. 1 (2020): 1-18, Full text picture_as_pdf

Introduction

Currently, the general public as well as scholars are reassessing the pontificate of Pope John Paul II. One of its significant weaknesses was his toleration of sexual abuses within the Church, which took place in dioceses throughout the world, including his native Poland. By contrast, many individuals praise how he left the traditional confines of Vatican walls and traveled to countries throughout the world. Likewise, many people appreciate his successful outreach to Jews that is seen as a significant change in Catholic-Jewish relations. John Paul met with Jews on many occasions during his visits to various countries. Wherever he visited, he always attempted to meet with representatives of the local Jewish communities. This resolve reveals his unique outlook toward Jews in comparison with previous popes, which ensued, at least in part, from his personal contacts with Jews over the years. The Polish Pope welcomed Jewish delegations to the Vatican. One of the first meetings he had as a Pope was with his schoolmate, Jerzy Kluger, the son of the head of the Jewish community in Wadowice, the native town of the Pope. He began to regularly meet his friend who had survived the Shoah and settled in Rome when he made his ad limina visits to Rome as bishop and then archbishop of Krakow.[1] The Pope’s last meeting with a group of visitors, on January 18, 2005, just several weeks before his death, was with a delegation of 130 Jews. It was on that occasion that Rabbi Jack Bemporad, the director of the Center for Interreligious Understanding of New Jersey, said, "No Pope has done as much or cared as much about creating a brotherly relationship between Catholics and Jews as Pope John Paul II." [2] This assessment is highly enthusiastic, but not untypical for Jews involved in a deeper dialogical relationship with the Roman Catholic Church. Other Jews might have been less excited, but the fact is that these meetings were remarkable. Without precedent, the Pope’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land was treated by the Vatican as a state visit. Likewise, the visit to the synagogue in Rome on April 13, 1986, was also an epoch-making event. The atmosphere during these visits was friendly and warm. It is not possible to question their significance without ill will.

Interestingly, some conservative theologians have questioned one of the Pope’s most famous utterances made during his 1986 visit to the Rome synagogue. Namely, the Pope said to the Jews present, "You are our dearly beloved brothers and, in a certain way, it could be said that you are our elder brothers." [3] The Pope must have taken the term "elder brothers" from the Polish Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz, who had used that term to refer to Jews over one hundred years earlier. [4] In the twentieth century, most Poles (including me), during their secondary education, studied Mickiewicz’s poetry and writing. While the statement seems sufficiently obvious, some commentators attempted to weaken it by stressing the alleged significance of the words "in a certain way." Such individuals argue that the Pope had no intention to refer to Jews as “elder brothers” officially, and those who had literally understood the phrase were mistaken. One can easily refute this claim by merely referring to the fact that the Pope publicly again repeated the same statement, with no hesitation. [5]

In this article, I attempt to describe and analyze the meetings that the Pope had with Polish Jews in Poland. I am uniquely prepared to discuss these meetings because I am the only Jew, and possibly the only person alive, who participated in all of these meetings. There were three of them: in 1987, 1991, and 1999. My approach is not merely personal. I have been actively involved in Christian-Jewish dialogue in Poland since the 1980s. At the same time, I have also been engaged in the academic study of the issues pertinent to this dialogue. [6]

The First Visit of John Paul II to Poland (1979)

As Pope, John Paul’s first of nine trips to Poland was the most influential, the most revolutionary, and the most memorable. Forty years ago, every aspect of his visit was new. As archbishop of Krakow, he was not widely known because the government-controlled media dedicated no coverage of him. The government censored the media, and the internet did not exist then. In the 1970s, Bishop Karol Józef Wojtyła (later Pope John Paul II) belonged to a Catholic intellectual circle that was close to broader oppositional intelligentsia circles. It is through these circles that I heard about Bishop Wojtyła. Yet, I had not met him, and until the day of his election as Pope, I would not have been able to recognize him. Everything changed when he was elected Pope, and the Communist authorities could no longer ban his presence from public life. His sheer presence began to undermine the walls that encircled us in the Communist-controlled public sphere. When the Pope came to Poland, millions went to welcome him, and this very fact caused the powerful and unexpected liberating experience of the possibility of freedom; being together to greet the Pope opened to us a vast amount of possibilities that we could only barely imagine. Crowds amassed in the streets. The feeling of solidarity was palpable. This experience was crucial to the process leading a year later to the establishment of the trade union “Solidarity,” which was de facto a massive antiCommunist movement.

There was no specific outreach to Polish Jews during this first visit. Yet, even at this point, I knew that Wojtyła had contacts with the leaders of the Jewish community in Krakow. I also soon learned that following the 1968 antisemitic campaign in Poland, Bishop Wojtyła insisted on using the occasion of visiting a church in Krakow’s Kazimierz district to enter a synagogue of that formerly Jewish neighborhood and be present while Jews were gathered for prayer.[7] His approach helped me to be present in a crowd engaged in a Catholic devotion.

While no direct Jewish dimension was present during the Pope’s first visit, I could only describe its significance by invoking biblical terms. Namely, the situation seemed to have a messianic dimension. I mean messianic in a broadly Jewish sense, not in the Christian one. I felt that this visit had initiated a breakthrough, a redemptive social change, a transformation that would reveal the noblest aspects of humanity. No later visit of the Pope had that aura, not even a shadow of it, at least for me. And this sort of messianic touch was present, at least to me, more broadly during the first period of the original “Solidarity” movement (1980-1981). Using the term messianic in this connection is very unusual and controversial. The presence and later complete disappearance of that dimension, that today feels unbelievable or like a bad joke, constitutes a separate subject, not to be continued here.

The Gesture (1983)

Before the first meeting between the Pope and Polish Jews took place in 1987, the Pope made a gesture during his second visit in 1983. On June 18, 1983, following a visit to the memorial at the Pawiak prison that had served as a place of torture during the World War II German occupation, the Pope stopped and left his car when he passed the Warsaw Ghetto monument. He approached the monument, knelt, and prayed for a few moments. The event had not been prearranged; it was outside the official itinerary. It seems that it was a spontaneous act, a gesture that probably came to his mind as an appropriate one when, at Pawiak, he was paying tribute to the victims of the Second World War.

The famous Rapoport monument, unveiled in 1948, is officially designated as the “Monument to the Heroes of the Ghetto.” I find this title improper. It suggests that the heroes are to be remembered, and the others, that is, the overwhelming majority of the Jewish victims, are somehow less important and less worthy of memory. Nevertheless, the monument has always been a focal point for the commemorations of all the victims of the Shoah. So, it was natural for the Pope to stop there.

In 1983, the site had an additional significance for me. Two months earlier, in April, the state as well as independent Polish groups marked the fortieth anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. There were two commemorations: the official one that included government representatives, leaders of Jewish institutions, and foreign Jewish guests; and an alternative one, created by us, the illegal-Solidarity and a group of oppositional Jewish activists that were associated with the underground Solidarity leaders. Marek Edelman, the surviving leader of the ghetto uprising and, recently, a Solidarity activist, supported the unofficial commemoration, but the police did not allow him to participate.[8] When I learned of the Pope’s gesture, I considered it as a support for the unofficial commemoration. Perhaps my interpretation was stretched, but such feelings came naturally; we felt the Pope was on our side even though the communist government tried to present his visit as an expression of support for the regime.

Tomasz Tomaszewski photographed the Pope’s stop at the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising monument, and he later published the photo in his book, Remnants, a collection of interviews with Polish Jews conducted by his wife.[9] The picture of the Pope in red attire kneeling at the monument is analogous to the 1970 gesture of West Germany’s Chancellor Willy Brandt. Yet, despite the visual similarity, the intention and the meaning of the Pope’s act was utterly different. Brandt sought to admit German guilt. The Pope wanted to show his solidarity with the victims. However, for us Poles, it was clear that he alluded to neither Polish nor Christian guilt. The book, Remnants, recounts the standard explanation, the gesture “symbolized for Poles and Jews alike the Pope’s desire for reconciliation between the two groups.”[10] As I will discuss below, the Pope expressed his attitude on this issue in 1987.

The Pope’s gesture before the Warsaw Ghetto Monument was the first specifically Jewish element during John Paul’s visits to Poland. Still, the Pope made another gesture before this time during his first visit. On June 7, 1979, when he visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp, he stopped at the memorial plaque in Hebrew alongside those in Polish and Russian and stressed the importance of what it symbolized. Yet, this action was momentary and only a tiny part of a long and detailed ritual at the camp, during which the Jewish aspect was otherwise absent. In 1983, the Jews were the focus of the Pope’s gesture when he knelt before the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial. Perhaps, at this time, the idea of a meeting between him and Polish Jews occurred to him.

The First Meeting (June 14, 1987)

On the last day of the Pope’s third visit to Poland, he met with a Jewish delegation in Warsaw in the residence of the Primate of Poland on Miodowa Street. I was a generation younger than my colleagues that included Dr. Szymon Datner, a respected historian and honorary president of the Religious Union of the Mosaic Faith,[11] Mozes Finkelstein, delegation chair and chairman of the Union board, Adam Flecker, a representative of the Union’s Szczecin branch, Michał Białkowicz, a Union office official, Czesław Jakubowicz, a Union representative from its Cracow branch, who had initially met the Pope when he was the archbishop of Krakow, and Zygmunt Nissenbaum, a Polish Jew living in Switzerland who, a few years earlier, had attempted to restore several Jewish cemeteries in Poland. None of my colleagues are alive today.

The atmosphere was sublime. Our chairman, Szymon Datner, captured this fact by quoting from Psalm 117 and Psalm 118 and then expressing how "proud, happy, and grateful" we were to be present at the meeting. [12] There was a feeling that it was a critical and historical event. "It is no exaggeration," continued Datner, "to ascribe to this event a historical dimension." Reflecting on this experience, today, I believe this feeling was unjustified since it did not have a significant impact on Christian-Jewish relations in Poland; still, the fact remains that it was the first such meeting in Poland. To me, it felt perfectly natural. The Pope seemed energetic and enthusiastic; all of us smiled; everyone seemed relaxed. Such an atmosphere was not to be felt during the later meetings, neither by me nor, I assume, by others.

Cardinal Franciszek Macharski in the presence of Archbishop Henryk Muszyński, the chair of a recently established sub-commission of the Polish Episcopate for Dialogue with Judaism, introduced us to the Pope. I presented the Pope with a book, Time of Stones, by my wife, Monika Krajewska, which featured photographs of Polish Jewish cemeteries. Composed of artistic black-and-white photographs and quotations from poetry, both biblical and contemporary, it was a unique book on the Polish market at that time. [13] I had hoped that it would make an impression on the Pope. Indeed, he examined several pages with keen interest.

I vividly remember my feeling of an authentic connection to the Pope. Despite the religious differences, we were connected in a way that seemed to me essential, deep, and lasting. There existed several links that are not easy to pinpoint. One had to do with the Christian-Jewish relationship in general and especially in Poland, another with our experiences of post-war Poland, and still another with the importance of the Shoah and World War II, again with a particular reference to Poland. The Polish intellectual ethos also united us, despite the denominational differences. Perhaps, the common denominator of all these points was due to our shared Polishness. I was Polish in a way similar to him being Polish. And my older Jewish colleagues could feel something similar, although probably in a significantly more limited way. This shared Polishness introduces a difference between me and the non-Polish Jews together with those Jews of Polish origin who do not share either the Polish cultural background or the experience of the post-war Polish realities.[14] This difference is real, even though many might ignore it. In important ways, it may be ignored. For example, during various meetings, the Pope functions primarily as the head of the Church rather than a Polish priest, and the Jews as members of the House of Israel rather than members of a specific national culture. Yet, at that particular 1987 meeting, the Polish dimension was overriding.

Despite that feeling of togetherness, I had ambivalent feelings when listening to the Pope’s address. There was no time to express my doubts; no real exchange followed. The Pope’s speech was improvised. On the official Vatican website, it exists in Polish and Italian only.[15] Here is an English translation:

Address of John Paul II to the Representatives of the Polish Jewish Community

First of all, I would like to thank you for this meeting which has become part of my program; it recalls many memories, many experiences of my youth, but certainly not only of mine. These were good and later dreadful, dreadful memories and experiences. Be assured, dear brothers, that the Poles and this Polish Church were nearby and watched the horrifying reality of the premeditated, total annihilation of your nation in a spirit of profound solidarity with you.

The threat against you was also a threat against us. The latter was not carried out to the same extent as there was no time to do so. It was you who suffered this terrible sacrifice of devastation. You suffered it also, one could say, for the others intended for devastation. We believe in the purifying power of suffering. The more atrocious the suffering, the greater the purification. The more painful the experiences, the greater the hope.

I think that the Israeli(te) nation today, perhaps more than ever before, is at the center of attention of the nations of the world. Above all this is because of that terrible experience itself, and also because through it, you have become a great voice of warning to all humanity, all nations, all the powers of this world, all systems and even every person. More than anyone else, you have become such a redemptive warning. I think that in this way you carry out your particular vocation, that you still prove to be heirs of that election to which God is faithful. This is your mission in the contemporary world to peoples, nations, all humanity. The Church, and in this Church, all peoples and all nations, feel united to you in this mission. They give prominence to your nation, your suffering, your devastation, when they wish to speak to men, to nations, to humankind with a voice of warning. In Your name, the Pope also speaks this warning. The Polish Pope has a special relationship to all this because, together with you, he was living all that in a certain way in this land.

This is just a thought that I wanted to share with you and to thank you for having come here for this meeting. There have been many meetings with your kinsmen in different countries of the world. For me, the visit to the Synagogue of Rome last year, the first after so many, many centuries, was unforgettable. I particularly value this present meeting in Poland; it is especially meaningful for me, and I think it will be particularly fruitful. It will help me and the whole Church to become more aware of what unites us, as my predecessor just said, in the realm of the Divine Covenant. This is what unites us in the contemporary world, in the face of the great tasks that this world places before us and before the Church in the field of justice and peace among nations. This is in accordance with your biblical word, "Shalom."

I thank you for the words spoken in the spirit of the Sacred Scripture, and in the spirit of faith in the same God, who is both yours and ours, the God of Abraham. And to you, to the few heirs of the great Israeli(te) community in Poland, apparently once the largest in the world, I offer the greeting of peace and my respect. Shalom! [16]

The main message at the beginning of this address is clear: the Church and the Poles, in general, confronted the murder of Jews with "profound solidarity." However, this statement is wrong. It was not the case that the sermons in the churches were exclusively pro-Jewish. Testimonies of that era and historical research reveal a great deal of indifference and antisemitism. Friendly gestures did exist, but they were not the norm. Perhaps the memories of Jewish survivors are too painful to recall the positive words, but hostility was easily encountered and defined the atmosphere in Poland for Jews. Since this is a fact, how can we understand the Pope’s words? Most probably, he tried to express his personal feelings about the Shoah and his sentiments during the war. I see no reason to question this. It is a moving testimony of his solidarity. Still, one must ask if it is correct for him to extend this attitude to the whole Church of that time and the entire Polish people.

The additional thesis he expressed is equally as strong: "the threat against you was also a threat against us." When I heard it, I immediately perceived it as highly inappropriate. Not only because of the blackmailers who were looking for hidden Jews to extort money from and then report to the Germans. What came to my mind first was the fundamental difference between fates. After all, the situation of Karol Wojtyła differed significantly from that of his Jewish classmates and other Jews. Only the Polish elites were endangered similarly as Jews. The Pope portrayed a picture of the possible mass murder of all Poles as if it were a reality, and only the lack of time made this other mass murder impossible. Again, he may have expressed the perception of the danger he felt because of the terror of the German occupation. Yet, to present this as a fact as if the fates of Jewish and non-Jewish Poles were the same, constitutes an unjustified move. Even in the hell of Auschwitz, the Jewish inmates, who were fortunate enough to survive the initial selection, lacked rights that others had, at least in theory, such as the right to correspond or to receive parcels. The Pope expressed his solidarity and his identification with the Jews attending the meeting, and in doing so, the difference of fates disappeared.

One might also perceive the Pope’s words as an attempt to "Christianize" the Shoah. This objection often appears in Jewish criticism of the Church’s dealings with the legacy of the Shoah. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Jewish commentators regularly made similar critiques during the Auschwitz Carmelite convent controversy. I find that such accusations are often made without proper justification. The Polish Pope certainly was aware of the relevant facts. He did not want to Christianize the Shoah but instead attempted to place the Jewish tragedy in a framework that would reveal its universal significance. This act, in itself, should not be reproached. In fact, we all do something like this in one way or another. At the meeting, the Pope described the horror of the Shoah by presenting it through the lens of a Christian theology of suffering. He spoke about the "sacrifice of devastation." The Polish term wyniszczenie translates as devastation; at the one end of its semantic field, it signifies "emaciation" and, at the other, "annihilation." According to the Pope, the tragedy was also present for the others "intended for devastation." Common in war-time Poland was the perception that the Poles were next in the queue to go to the gas chambers after the Jews. In addition, the Pope expressed another idea that Jews were the innocent victims who served as substitute victims for other possible victims of evil. He theologizes the Shoah. He suggests that God has chosen Jews to suffer in the place of humanity. As a result, Jews "have become a redemptive warning." He states that it was a way of fulfilling the Jewish mission resulting from the biblical covenant. And he declares the Church’s solidarity with Jews in that it feels "united with you in this mission."

This interpretation was challenging for me to accept, despite the feeling of unity that was so palpable. Yet, while I do not share this Christian interpretation, it might serve a useful purpose. At the very least, it stresses the continuity of the election of Israel. While many Jews would not be pleased by the Pope’s interpretation, I do not think it is inherently wrong. The idea of the plight of Jews being the litmus test for the health of the whole society is not uncommon among Jews and is related to the Pope’s approach. Much more problematic is another aspect of his theology of suffering. He put it in the most explicit terms, “We believe in the purifying power of suffering. The more atrocious the suffering, the greater the purification. The more painful the experiences, the greater the hope.” Such understanding comes close to an apotheosis of suffering, which may be theologically attractive to Christians, but seems overly simplistic to me. Suffering might produce positive results, but often it does not. Against the papal claim, I believe that there is no guarantee that a redemptive quality will emerge from suffering. The statement relates to a theological position but does not express empathy. The ordeal of the victims was virtually ignored. As Rabbi Irving Greenberg has queried (and this applies equally well to some Jewish interpretations of the Shoah): Would you be able to state your interpretation while looking at the bodies of children burning in a camp crematorium? If not, it would be better to refrain from theologizing and remain silent.

When I heard the Pope’s remarks, I reacted with similar feelings expressed above. Over time, my feelings grew stronger. Yet, I did not immediately articulate them. I was fascinated by John Paul and, above all, I much appreciated his respect for Judaism and Jewish experiences. After several years an additional interpretation emerged. The most divisive discrepancy, that is, his attitude to suffering, could be viewed from my perspective in a way that would drastically reduce the theological opposition. Namely, I could interpret suffering not as meaningful as such, which could justify the tragedy at the root of the suffering, but as a challenge. The theology of suffering may differentiate Jews from Christians—and this difference remains rather theoretical than practical as hardly anyone desires to suffer—but challenges are often common to all of us. Emil Fackenheim’s famous formulation of a 614th commandment (added to the traditional 613) forbids a Jew to abandon Judaism since doing so brings a posthumous victory to Hitler. I believe this formulation aptly describes a prevailing attitude among Jews. We can interpret the words of the Pope similarly. When he sees a “redemptive warning” in our suffering in which we “prove to be heirs of that election, to which God is faithful,” it can be seen as a challenge to remain faithful. Thus his words do not necessarily need to be seen as an affirmation of suffering but rather as an appeal for Jews to remain faithful to the Covenant.

One more point struck me in the Pope’s speech. He avoided the term "Jew" and used "Israeli(te)" instead. I felt his calling us wspólnota izraelska or Israeli(te) community was strikingly inappropriate.[17] Even those of us Polish Jews who felt a strong bond to the State of Israel were not Israelis. In fact, we often felt the need to oppose the Israeli envoys who were ready to treat us as a sort of incomplete Israelis. The Pope’s language could also suggest that he regarded the word "Jew" as pejorative, anachronistic, or shameful. Yet, I did not draw this conclusion since I knew that he did use the name on other occasions. For example, at our second meeting, in 1991, he used the words "Jew" and "Jewish community" even though he also repeated his 1987 term, "Israeli(te)." How can we interpret his language? Perhaps it expressed a pro-Zionist attitude? Maybe it did, but I suspect that it was primarily a way to stress the biblical dimension of our identity. "Israel" would mean "the House of Israel" rather than "the State of Israel." This interpretation is consistent with the general framework of the meeting in that only the representatives of the religious Jewish community were invited; the leaders of the numerically stronger secular organization were ignored.

The Visit that Did Not Materialize

Before turning to the second meeting, it is worthwhile to describe a failed opportunity for an additional meeting. In their preparation for the Pope’s 1991 journey to Poland, Vatican envoys asked the Polish Jewish community whether it would be possible to arrange for the Pope to visit the Nożyk synagogue in Warsaw. The attempt was confidential. I learned about it some ten years later, when Father Professor Michał Czajkowski, then the co-chair of the Polish Council of Christians and Jews, and I visited the nuncio, Archbishop Józef Kowalczyk. In 1991, the Vatican representatives approached Rabbi Pinchas Menachem Joskowicz, the Chief Rabbi of Poland, about the visit.

In 1988, Joskowicz had been nominated for the chief rabbinate and Poland was still under communist rule. The appointment resulted from an arrangement between the Polish government with prominent American Jews. In particular, Rabbi Chaskel Besser, a Bobover Chassid who spoke beautiful Polish and had a broad education, represented the Lauder Foundation in these discussions. Rabbi Besser much desired to assist Jewish religious life in Poland and, in addition to Joskowicz, sent Rabbi Michael Schudrich, then a Conservative rabbi, to Poland. Later, Schudrich became the Chief Rabbi of Poland. I met Rabbi Joskowicz in mid-1988 when I joined Rabbi Besser on a visit to the center of the Chabad movement in Brooklyn. At this point, it was already agreed that Joskowicz would go to Poland. Joskowicz was a Polish Jew and a survivor of Auschwitz, who now lived in Israel and had not recently functioned as a rabbi. He was a Chassid, with no secular education, so he represented a traditionalist approach to Judaism. His traditionalism was not problematic for the Jews attending the synagogue in Warsaw. They were all traditionally educated before the war and only later pursued secular careers, often in the army. It was only after 1968 that some of them returned to active Jewish life. For them, Orthodox Judaism was the only variety they knew, so they did not question a rabbi stemming from such an environment. By contrast, for my generation, a rabbi with no secular education was hardly an appropriate choice. We could relate to him in some respects, but cultural differences between us made it difficult to attain a deeper understanding.

The characteristics of the rabbi are highly relevant to the topic at hand. Not surprisingly, when he was asked about the prospect of the papal visit to the synagogue, he refused. He replied that there were not enough Jews in Warsaw. “Who would be sitting in the pews?” he asked. In his opinion, the assimilated, nonreligious Jews were not the right audience. Was this the reason or just a pretext? I suspect that the idea of a priest, let alone a Pope, in the synagogue seemed too much for him. He probably was afraid that the visit would not be condoned by the Israeli ultraorthodox leaders who were his main point of reference.

At that time, no one else knew about the initiative. No one else was asked because the leadership of the Church assumed then—and this is still mostly the case—that their partners were primarily rabbis. This presumption was a mistake. The misunderstanding of the role of rabbis in Judaism is common among Catholics. They assume that a rabbi is equivalent to a priest in the Church, which is a highly misleading perception. While there are rabbis who are spiritual leaders with significant authority, generally, a rabbi is employed by a community as an expert in the field of religious law. In our case, it was even more complicated because the community had little to do with Rabbi Joskowicz’s nomination. He was brought to Poland by a government agency at a time when the government and the political system it represented began to disappear. The Rabbi’s gratitude to the government of the “Polish People’s Republic” published in the Jewish calendar and yearbook for 5750, or 1989-90, well-illustrated this situation. On behalf of Jews, Rabbi Joskowicz thanked the government for its “assistance to bring a spiritual leader to the Jewish community.”[18] The source of his position is thereby clearly indicated. Ironically, by the time the calendar went into effect, the government and the “Polish People’s Republic” were no longer in existence. I am not claiming that the Jews who attended the synagogue did not accept the rabbi. However, I do believe that if the Vatican representative had consulted with the leadership of the community, it would have given a different answer. I assume that the president of the Union’s board, Dr. Paweł Wildstein, and the majority of the synagogue members, would have been in favor of the Pope’s visit. I am quite sure that they would have asked me to help prepare the visit because, despite the generational gap, we were cooperating closely. I was already active in the Polish Council of Christians and Jews, which I helped to establish. The council was not approached. In the end, the missed opportunity could be blamed not only on Rabbi Joskowicz but also on the leadership of the Catholic Church.

The Second Meeting (1991)

On June 9, 1991, the second meeting took place in the residence of the Apostolic Nuncio instead of the Nożyk synagogue. Again, it was held on the last day of the Pope’s visit. Without attributing too much to this fact, one might interpret the meeting with Jews as not of the highest priority for the Polish organizers. I am confident that if it were not for the Pope’s determination, other possible meetings would have taken place rather than the Jewish one. At the same time, there is no reason to believe that the meetings with Jews were of top priority for him. More probably, they ware rather like an addendum to the main program.

In the Jewish delegation, there was one more person of my generation, Konstanty Gebert, a well-known journalist. Mozes Finkelstein, who had been present at the 1987 meeting, also joined us again. By then, Dr. Datner had passed away. Another leader of the Union, retired colonel, Dr. Paweł Wildstein, joined along with two other persons, Szymon Szurmiej, the chairman of the secular, formerly communist-dominated, Social-Cultural Association of Jews in Poland, and Michał Friedman, another retired colonel and then the chairman of the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute, who was also a noted translator of Yiddish and Hebrew literature into Polish. While religiously educated, Friedman did not attend synagogue. Unlike in 1987, this time, non-religious Jewish leaders were included. This step was a significant development because, after all, the distinction between more and less religious Jews is of no fundamental importance in our tradition, even though it may be of practical importance.

Archbishop Henryk Muszyński introduced us. Michał Friedman spoke on our behalf. He expressed our feelings saying that “with the entire Polish nation, we share joy and pride because our compatriot stands at the head of the Church." [19] Friedman noted that the Pope understood so well "the complexity of Polish-Jewish relations," and stressed the creativity of Jewish life in Poland and the contribution of Jews to Polish culture and Polish military efforts. He also praised the pastoral letter of the Polish Episcopate of November 30, 1990. He proclaimed that antisemitism is especially harmful to Poland; indeed, "today it is nothing other than antiPolonism." Friedman attributed antisemitism to a lack of education, and displayed his erudition by quoting Shemot Rabbah, "Woe to the house that has windows open to darkness." He also said that while the Shoah is a crucial reality for us, Poland is for us more than a cemetery. Finally, he expressed the hope that Vatican-Israel relations would be normalized.

During this meeting, the Pope was weaker than in 1987, and the atmosphere was not as elevated as before. The lack of equal enthusiasm was also due to the general circumstances of the visit. The Pope was unsatisfied with the developments in free Poland after 1989. Under democracy, the Church was not as dominant as he would have hoped. Similarly, he feared that liberal values were taking root. In a recently published diary, a Catholic friend remarked that "Poland was experiencing a bourgeois revolution and [the Pope] spoke as if it was a counterreformation." [20] Nevertheless, the authority of the Pope remained unsurpassable.

The Pope was tired, but he spoke longer than before, this time using notes. The address was much more standard. First, he said that he always meets with representatives of Jewish communities because we are uniquely linked by faith. Next, he expressed satisfaction that he could meet Polish Jews "on Polish soil," and mentioned the “glorious and tragic past” of Polish Jews. Then he quoted verbatim a central point of his 1987 address, "I and the overwhelming majority of Poles were helplessly watching the horrific crime against the Jewish people, sometimes without the full knowledge of the events" in the “spirit of profound solidarity with you. The threat against you was also a threat against us. The latter was not carried out to the same extent as there was no time to do so. It was you who suffered this terrible sacrifice of devastation. You suffered it also, one could say, for the others intended for devastation.”

The Pope reaffirmed his previous point but did not repeat the theology of suffering. This change of approach made the claim somewhat less problematic, but I am unable to say whether this was the Pope’s intention. He then stressed his solidarity with the November 1990 pastoral letter of the Polish Episcopate by quoting from it, “The same land, which for centuries was the common fatherland of Poles and Jews, of blood spilled together, the sea of horrific suffering and injuries shared, should not divide us but unite us. For this commonality cries out to us, especially the places of execution and, in many cases, common graves.” [21]

The pastoral letter restated the teachings of Nostra Aetate and quoted extensively John Paul II, including the claim, “The threat against you was also a threat against us.” The pastoral letter also made other claims regarding the Second World War. It tried not to ignore the facts of collaboration, but how it was handled struck me as ineffective. While it did say, “We express our sincere regret for all the incidents of antisemitism, which were committed at any time or by anyone on Polish soil,” it also said, “We are especially disheartened by those Catholics who, in some way, were the cause of the death of Jews. They will forever gnaw at our conscience on the social plane. If only one Christian could have helped and did not stretch out a helping hand to a Jew during the time of danger or caused his death, we must ask for forgiveness of our Jewish brothers and sisters.”

The suggestion implied by this formulation was that the indifference to the fate of the Jews was exceptional, and this is a grossly misleading claim. The Pope did not address this point nor other issues discussed in the pastoral letter. Instead, he said that the Shoah emboldened “the nations of Christian civilization” to remove anti-Jewish “prejudices and other expressions of antisemitism.” Finally, he reaffirmed that the teachings of the Second Vatican Council must continue to be introduced into the life of the Church.

At the brief meeting afterward, he said that the establishment of the State of Israel was an act of historical justice. Still, the situation was such that the general normalization of the Vatican-Israeli relations could not yet be achieved.

The atmosphere at the meeting was amicable, so the appeal of the pastoral letter repeated by the Pope that “the blood spilled together, the sea of horrific suffering …should not divide us but unite us,” was received with sympathy. Yet, it is clear that to say “should” is easy, but to act according to it is not. The memory of the Shoah remains divisive, and a considerable effort and the courage to face the dark realities are needed to diminish the division. At that time, neither the Pope nor anyone in the leadership of the Polish Catholic Church sensed the depth of the tensions between Polish Jews and Christians. A few years later, the writing of Jan Gross would unleash them by uncovering the tortured history of collaboration and antisemitism among Christian Poles toward their Polish Jewish neighbors under the National Socialist occupation. [22]

Our 1991 meeting contributed to the emerging respectability of Jews and, in particular, religious Jews in Poland. In that period, meeting with the Pope provided an instant, if momentary, nobility. This fact was of crucial importance for the process that I call “de-assimilation,” or the move opposite to assimilation, a gradual reappropriation of a stronger Jewish identity of one sort or another.[23] For some people of my generation, this process began in the 1970s and expanded in the 1980s. In the early 1990s, it increased even more when we started to enjoy political freedom. Many individuals in Catholic intellectual circles were interested in the Jewish culture and religion, and this was also helpful. Similarly, the outreach of the Pope toward Jews significantly enhanced the process of de-assimilation because it meant the main-streaming of Jewish presence, culture, and religion. In turn, such a positive atmosphere made it easier for Poles of Jewish heritage to see involvement in Jewish public life as a respectable option for them.

The Third Meeting (1999)

The third meeting was different from the previous ones. It was a public gathering at the Umschlagpltaz monument in Warsaw, marking the place from which 300,000 Jews had been deported to be murdered in Treblinka death camp. The Jewish delegation was inside the memorial. It included many people, from Marek Edelman, who had been a commander during the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, to people of the post-war generation headed by Jerzy Kichler, the chairman of the board of the Union of Jewish Religious Communities. Crowds of people made any exchange hardly possible. The Pope was weaker. Still, he read a remarkable prayer for the Jewish people. The words of this prayer were later printed as small leaflets together with the 1986 photograph of John Paul II warmly greeting Rabbi Elio Toaff in the Rome synagogue. A Jewish publisher from Switzerland supported the printing of more than one million copies of the leaflet, which were distributed at appropriate occasions over many years. [24]

The meeting could have had a much more significant impact had it not been for an unexpected event that took place on the same day in the building of the Polish parliament. Rabbi Joskowicz approached the Pope and asked for the removal of the large cross from the area adjacent to the Auschwitz camp. A former inmate in Auschwitz, the Rabbi said, he “could still hear the crying of the children.” Polish media televised the incident live, and it completely overshadowed the subsequent meeting at the Umschlagplatz. Many Jews were embarrassed not so much by the contents of the appeal as by its form. In clumsy Polish, the Rabbi said, “I ask Mr. Pope to give a call to his people to take this cross away from the camp.”[25] The very term “Mr. Pope” was bad enough. To make it even worse, the Rabbi was gesticulating in a way that might be perceived as threatening to the Pope. He was appealing rather than threatening, but antisemites used a photograph taken at the scene to demonstrate so-called Jewish attacks on the Pope and Christianity. A few days later, the Rabbi lost his position and returned to Israel.

The Pope’s prayer at Umschlagplatz is noteworthy. I am grateful for it but wish to comment upon it. It begins,

God of Abraham, God of the Prophets, God of Jesus Christ.

You in Whom all is included,

You towards Whom everything moves,

You, Who are the end of everything.

Hear our prayers for the Jewish People,

whom you still consider dear because of their forefathers. [26]

The stress on the phrase “because of their forefathers” might be perceived as critical of present-day Jews because it can imply that they are not worthy of cherishing. However, this language is precisely the traditional Jewish way of describing the situation. We are not supposed to see ourselves as worthy. It is only due to the merit of our ancestors that we benefit. I see no reason why the Pope cannot use this insight. The very fact that the Pope describes Jews as “still” cherished and dear to God is essential and positive.

What the Pope said next is not entirely clear to me because two versions exist. The shorter one, included in the text of the leaflet, says,

Awaken in them a constant and ever-more-vital desire to follow Your truth and Your love.

The more extended version[27] that the Pope probably uttered on June 11, 1999, reads:

Grant them deep awareness of belonging to one human family, created by You and supported by You.

Awaken in them a constant and ever-more-vigorous desire to follow Your truth and Your love. Grant them the ability through human solidarity to move beyond prayer to practice social justice, assisting others in their search for You. Allow each of its members to build community, according to Your redemptive plan, through personal honesty, correctness of morals in private and public life, and respect for life and family.

No matter the exact version, I can concur with all of these prayers. Then the Pope invoked the specific Jewish mission:

Assist them, so that their search for justice and peace may reveal to the world the power of Your blessing.

This prayer is an acceptable way of expressing the Jewish mission. For some Jews, it may sound problematic because the traditional Christian interpretation links the goal with the sacrament of baptism. An individual could detect this hope in the Pope’s words. However, I believe that John Paul did not mean anything of this sort. As the next sentence reveals, before he explained his understanding of the Jewish mission, he first expressed his empathy for the victims of the Shoah, which was particularly relevant because of where he recited the prayer:

Support them, so that they may know love and respect from those who still do not understand the extent of their sufferings, and from those who in solidarity and concern share in the pain of the wounds that have been inflicted on them.

And then comes the sentence that I understand as an appreciation of a distinct Jewish path of life, separate from that of Christians:

*Remember their new generations, so that they may continue to be faithful to You and remain open to Your transcendence, by exemplifying the special mystery of their vocation. [28]

The very phrase "the special mystery of their vocation," is profound. [29] For the Pope, the Jewish mission has a universal aim. I concur entirely with his words,

Help their testimony make humankind understand that your plan of redemption includes all humanity and that You are the beginning and the ultimate goal for all peoples. Amen.

The prayer is perfectly appropriate for the occasion. In a place that memorializes the murder of the overwhelming majority of Polish Jews, the Pope spoke words affirming a supra-historical value of Jewish existence, its unique character apart from Christianity, and its deep connection to the lives of all human beings. The Pope’s prayer presents Jewish life as a mission that is of fundamental importance not only for Jews but for the entire world. I find that all the doubts and objections regarding John Paul’s attitude toward Jews and Judaism lose their power, given the prayer at the Umschlaglplatz. One can only repeat the striking words, “Pope John Paul II was indeed the Pope of the Jews.” [30]

Popes Benedict XVI and Francis have continued the approach begun by John Paul II. At the same time, Poles, in general, received the pro-Jewish message of the Polish Pope in a highly ambivalent way. The prayer has impacted some Poles, but those who continue to be antisemitic still claim that they are following the Pope’s teachings. The appropriation of John Paul by virtually all currents within the Polish Catholic Church makes his actual teachings about Jews and Judaism almost irrelevant. However, I trust that the time will come when his genuine attitude toward Jews will become a model for Catholics in Poland and beyond.

Stanisław Krajewski picture_as_pdf

Przypisy

[1] The relationship is well described by Darcy O’Brien in the book The Hidden Pope: The Untold Story of a Lifelong Friendship That Is Changing the Relationship Between Catholics and Jews - The Personal Journey of John Paul II and Jerzy Kluger (NY: Daybreak Books, 1998).

[2] Jewish Telegraphic Agency, “John Paul II meets large Jewish group in Vatican,” January 19, 2005.

[3] John Paul II, Address at the Great Synagogue of Rome, April 13, 1986. (Pl)

[4] In the 1848 text, “Skład zasad,” Mickiewicz wrote, “Izraelowi, bratu starszemu, uszanowanie, braterstwo, pomoc na drodze ku jego dobru wiecznemu i doczesnemu. Równe we wszystkim prawo, which means “To Israel, the elder brother, respect, brotherhood, assistance in its way to eternal and worldly good. Equal rights in every respect,” Mickiewicz, Dzieła, vol. 12, ed., S. Kieniewicz (Warszawa : Czytelnik, 1997), 10. Mickiewicz took the term probably from one of his mentors, a Messianic visionary, Andrzej Towiański, also a Polish émigré in Paris. This source of the term provides a convincing argument that it is wrong to criticize the Pope, as is sometimes done, for the alleged reference to the recurrent biblical motive of the primacy of the younger sibling, that is, the Church over the Jews.

[5] In Poland, this polemic has been going on since 2009. In an interview for a Catholic weekly, Father Waldemar Chrostowski expressed his great satisfaction at the statement by the then editor-in-chief of L’Osservatore Romano that it was no longer correct to refer to Jews as “elder brothers,” Idziemy 43 (October 25, 2009), 4. This position was criticized by Zbigniew Nosowski, who wrote, "Still Elder Brothers", Idziemy 45 (November 8, 2009), 38, and by Father Alfred Wierzbicki, who remarked that thePope’s words were more binding than those of a Vatican journalist, Idziemy 46 November 15, 2009, 38. In a paper analyzing the polemic, Marek Nowak, OP, presented a theological argument in favor of the “elder brothers” thesis, saying that it is a way to express the permanence of the covenant with Israel. On this point, see Nowak, “Starsi bracia czyli trwanie przymierza", in Żydzi i judaizm we współczesnych badaniach polskich, vol. 5, ed. K. Pilarczyk, (Krakow: Polska Akademia Umiejętności, 2010), 327343. Nowak quotes several subsequent statements by the Pope expressing the same idea without relativizing it. See Pope John Paul II, Crossing the Threshold of Hope (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994, p. 99), in which he writes that it is correct to look to “the Jews as our elder brothers in the faith.” In a reply to Nowak, Chrostowski maintained that the “elder brother” formula is incorrect because it ignores the discontinuity introduced by Rabbinic Judaism with respect to the Biblical Judaism. See Chrostowski, “Żydzi jako “starsi bracia” chrześcijan. Markowi Nowakowi w odpowiedzi,” in: Żydzi i judaizm we współczesnych badaniach polskich, vol. 5, 345-360. It is worthwhile to note that even in 2020 all the individuals above continue to be active in Poland. Chrostowski is the chairman of Polish theologians, Nosowski is a co-chair of the Polish Council of Christians and Jews (CCJ), Nowak is on the board of the Polish CCJ, and Wierzbicki is a professor at the Catholic University in Lublin.

[6] I have functioned as a Jewish dialogue partner to official Church institutions and committees since the mid-1980s, and co-chair of the Polish Council of Christians and Jews since the founding of the council (initially under another name) in 1989. Since the mid-1990s, I have also been a professor of philosophy at the University of Warsaw, studying and teaching, among other things, the philosophy of dialogue and interfaith relations.

[7] See Jacek Moskwa, Droga Karola Wojtyły, tom 1, Na tron apostołów 1920-1978 (Warsaw: Świat książki 2010), 315.

[8] The two commemorations are presented at the core exhibition in Polin, the Warsaw museum of the history of Polish Jews.

[9] Malgorzata Niezabitowska, Remants. The Last Jews of Poland (NY: Friendly Press, 1986), 261.

[10] Ibid., 260.

[11] In Polish, Związek Religijny Wyznania Mojżeszowego. Created in 1949, it was completely controlled by the government agency Urząd do spraw Wyznań (Office for Denominational Affairs) even though most of the funding for its activities came from the American Joint Distribution Committee. In 1987, it consisted of sixteen local congregations. In 1992, after the political transformation, its rather peculiar name was changed when the union was transformed into Związek Gmin Wyznaniowych Żydowskich w RP or The Union of Jewish Religious Communities in the Republic of Poland.

[12] These words and the next quote are my translation of Datner’s utterances available in the report published in “Kalendarz żydowski 5749/1988-89”, the calendar and yearbook published by the Religious Union of Mosaic Faith, 1988, p. 182.

[13] The book Czas kamieni (Warsaw: Interpress, 1983) had been completed in 1981 during the thaw of Solidarity. It appeared only in 1983, in four languages, Polish, English, French, and German. A revised English version, A Tribe of Stones, appeared in 1993.

[14] On this point, see Poland and the Jews. Reflections of a Polish Polish Jew (Cracow: Austeria, 2005).

[15] See the Polish original and the Italian version. The Polish text was also published in Wiara i odpowiedzialność. Religia. Społeczeństwo. Historia. Kultura 8 (1987), and in Kalendarz żydowski 5749/1988-89 (Warsaw, 1988), 182-183, the calendar and yearbook published by The Religious Union of Mosaic Faith.

[16] I am grateful to Sue Throckmorton for her assistance with the translation. An English translation has been published on the site of the Centre for Dialogue and Prayer in Oświęcim(that is, Auschwitz). However, this translation is not completely faithful to the original, and in order to substantiate my analysis I prefer to use my own translation. To indicate the inaccuracies let me offer two examples: first, the use of the present tense rather than the original past tense in the sentence in the first paragraph, about the Polish and Church’s solidarity with the murdered Jews; second, the use of the term "the nation of Israel" rather than "Israeli" or "Israelite" nation, the adjectival form of the original.

[17] Whether the adjective "Israeli" or "Israelite" serves as a better translation is debatable. The plain meaning is "Israeli," but here it rather means “belonging to the House of Israel,” so, perhaps, “Israelite” is more proper.

[18] Kalendarz żydowski - Almanach, 5750, 1989-1990 (Warsaw: The Religious Union of the Mosaic Faith), 199.

[19] See Kalendarz żydowski-Almanach, 5753, 1992-1993 (Warsaw: The Religious Union of the Mosaic Faith, 1992), 171-172 (Author’s translation).

[20] Tadeusz Sobolewski, Dziennik. Jeszcze jedno zdanie (Warsaw: WAB, 2019), 272.

[21] See:

[22] See Jan Tomasz Gross, Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001), originally published in Polish as Sąsiedzi: Historia zagłady żydowskiego miasteczka (Sejny: Fundacja Pogranicze, 2000).

[23] In the 1990s, I used the term “de-assimilation” in “Jewish De-assimilation in Poland: A Personal Perspective,” in Bulletin SIDIC (Service International de Documentation Judéo-Chretienne), 32:2 (1999), 7-11. A more comprehensive description is contained in my article, “My wszyscy z niej: dezasymilacja polskich Żydów,” in Co się dzieje z polskim społeczeństwem? Księga jubileuszowa dedykowana Profesorowi Ireneuszowi Krzemińskiemu, ed., Urszula Kurczewska, Małgorzata Głowania, Wojciech Ogrodnik, and Dominik Wasilewski (Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2019), 297-309.

[24] At the Polish site of the Notre Dame de Sion it is stated that “the prayer was written at the request of Mr. Steven Goldstein, whose parents were Jews from Cracow, who paid for the printing of a million copies of the prayer juxtaposed with the photograph of John Paul II meeting with Rabbi Toaff in the synagogue in Rome. They were distributed before the Day of Judaism in 2001.” According to Barbara Sułek-Kowalska (personal letter) the whole action was made possible due to Sister Dominika Zaleska, NDS, and was coordinated by Bishop Stanisław Gądecki.

[25] See New York Times, June 2, 1999. For a thorough exploration of the cross at Auschwitz and the related Carmelite convent controversy, see Carol Rittner and John K Roth, eds,Memory Offended: the Carmelite Cross Controversy(Westport, CT: Praeger, 1991), especially 117-134.

[26] Prayer of Pope JP II for the Jewish People.

[27] See, (author’s translation).

[28] The phrase in italics belongs to the longer version and is not included in the text of the leaflet.

[29] Unfortunately, this part, present in the text of the leaflet, is shortened in the English version at the site of the Auschwitz Centre for Dialogue and Prayer. There the text ends with "Remember about the new generations, about young people and children, so that they understand that your plan of redemption includes all humanity and that You are the beginning and the ultimate goal for all peoples. Amen."

[30] This was said in the present tense by Rabbi Jacques Bemporad after the reception in the Vatican in 2005.