Wikipedia’s Intentional Distortion of the History of the Holocaust

By an ideologically motivated group of Wikipedians (people very active in writing or changing Wikipedia entries)

10/02/2023 | Na stronie od 03/03/2023

Source: uOttawa and Times of Israel

Wikipedia entries related to the history of the Holocaust in Poland are being manipulated by an ideologically motivated group of Wikipedians

More:

- Piotr Konieczny responds to an article by prof. Jan Grabowski and prof. Shiry Klein. Wyborcza.pl ALE HISTORIA (Piotr Konieczny odpowiada na artykuł autorstwa prof. Jana Grabowskiego i prof. Shiry Klein.)

- Main response to Grabowski and Klein. Volunteer’s Substack

- Na prośbę Pana Richarda Tylmana umieszczam link do jego odpowiedzi na artykuł prof.Jana Grabowskiego opublikowanej na stronie Academia.edu pt.: "The Holocaust and Wikipedia's Portrayal of the Polish-Jewish Relations" by Richard Tylman (https://www.academia.edu/116723369/The_Holocaust_and_Wikipedias_Portrayal_of_the_Polish_Jewish_Relations). Pan Richard Tylman jest jednym z anglojęzycznych wikipedystów omawianych przez prof. Grabowskiego. Jego strona w angielskiej Wikipedii znajduje się pod adresem: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Poeticbent

A new study co-led by Jan Grabowski, a history professor in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Ottawa and Shira Klein, associate professor of history at Chapman University in California, found that Wikipedia entries related to the history of the Holocaust in Poland are being manipulated by an ideologically motivated group of Wikipedians (people very active in writing or changing Wikipedia entries). Their goal is to distort and falsify the history of the Holocaust in a way which reflects the vision of history espoused by Polish nationalists.

“In the cases which we analysed in our article, the complicity of Poles in the Holocaust, or the participation of ethnic Poles in anti-Jewish acts, is being downplayed or denied,” says professor Grabowski, a recipient of the prestigious 2022 SSHRC Impact Insight Award. “Simultaneously, the role of Poles in rescuing the Jews during the Holocaust is being inflated to a great degree. At the same time, the nationalistic Wikipedians spread and propagate antisemitic cliches and stereotypes.”

The article contains two parts: the first one looked at what entries/facts/interpretations are being distorted and falsified and the second part looked at the behind-the-scenes processes and editorial mechanisms inside the Wikipedia which allow small groups of people with an ideological axe to grind to take control of the information consumed by millions of Wikipedia users.

“The entries which we looked at are read by hundreds of thousands of readers per month,” explains Jan Grabowski. “We also show how such a small group of Wikipedia insiders makes it practically impossible to restore the balance to the Wiki entries and to correct the distortions and falsifications.”

The study Wikipedia’s Intentional Distortion of the History of the Holocaustnorth_eastexternal link was published in The Journal of Holocaust Research.

Wikipedia’s Intentional Distortion of the History of the Holocaust

Jan Grabowski &Shira KleinORCID Icon Published online: 09 Feb 2023

ABSTRACT

This essay uncovers the systematic, intentional distortion of Holocaust history on the English-language Wikipedia, the world’s largest encyclopedia. In the last decade, a group of committed Wikipedia editors have been promoting a skewed version of history on Wikipedia, one touted by right-wing Polish nationalists, which whitewashes the role of Polish society in the Holocaust and bolsters stereotypes about Jews. Due to this group’s zealous handiwork, Wikipedia’s articles on the Holocaust in Poland minimize Polish antisemitism, exaggerate the Poles’ role in saving Jews, insinuate that most Jews supported Communism and conspired with Communists to betray Poles (Żydokomuna or Judeo–Bolshevism), blame Jews for their own persecution, and inflate Jewish collaboration with the Nazis. To explain how distortionist editors have succeeded in imposing this narrative, despite the efforts of opposing editors to correct it, we employ an innovative methodology. We examine 25 public-facing Wikipedia articles and nearly 300 of Wikipedia’s back pages, including talk pages, noticeboards, and arbitration cases. We complement these with interviews of editors in the field and statistical data gleaned through Wikipedia’s tool suites. This essay contributes to the study of Holocaust memory, revealing the digital mechanisms by which ideological zeal, prejudice, and bias trump reason and historical accuracy. More broadly, we break new ground in the field of the digital humanities, modelling an in-depth examination of how Wikipedia editors negotiate and manufacture information for the rest of the world to consume.

Introduction

This essay will show how the English-language Wikipedia, the world’s largest encyclopedia, whitewashes the role of Polish society in the Holocaust and bolsters stereotypes about Jews. We will show how a handful of editors steer the historical narrative away from evidence-driven research toward a skewed version of history touted by right-wing Polish nationalists. Throughout Wikipedia’s numerous articles on Polish–Jewish relations, there are dozens of statements that deviate from historical fact, and which, in the aggregate, perpetuate potent myths about Polish–Jewish relations before, during, and after the Holocaust. We will also explain why it is so difficult to counter the impact of these editors and conclude with some suggestions to rectify this problem.

This essay contributes to the area of Holocaust memory, revealing the digital mechanisms by which ideological zeal, prejudice, and bias trump reason and historical accuracy. More broadly, our study breaks new ground in the field of the digital humanities, modeling an in-depth examination of how Wikipedia editors negotiate and manufacture information for the rest of the world to consume. Quantitative studies researching Wikipedia are plentiful, ranging from big-data analyses of citation patterns to large-scale surveys on editors’ gender gap and measurements of Wikipedia’s web traffic.Footnote1 While important in their own right, quantitative studies cannot identify Wikipedia’s distortions, juxtapose article content with scholarship, or evaluate the intentionality of misinformation. A few seminal studies have taken just such a qualitative approach, each dissecting a handful of Wikipedia articles.Footnote2 Our research, however, examines Wikipedia’s portrayal of an entire historical subfield, namely, the Holocaust in Poland.

This study is the first of its kind both in scope and method: we examine 25 public-facing Wikipedia articles (known as mainspace pages) and nearly 300 of Wikipedia’s back pages, including talk pages (where editors discuss articles), noticeboards (where editors ask questions and request assistance), diffs (where the system displays the difference between versions of the same Wikipedia page), and arbitration cases (where editors take their disputes). We complement these with interviews of editors in the field and statistical data gleaned through Wikipedia’s tool suites. This study lays the ground for researchers in other fields to trace the vast universe of Wikipedia’s mainspace and back pages and illuminate the production of digital knowledge.

Why should we care so much about Wikipedia? Most scholars would say that there’s no expectation Wikipedia should be reliable in the first place; that’s what peer-reviewed scholarship is for. Yet, the importance of Wikipedia is tremendous because of its visibility. Wikipedia is the seventh most visited site on the internet, with 7.3 billion views a month.Footnote3 Its articles show up in over 80 percent of the first page of search engine results and over 50 percent of the top three results. Browser searches yield more links to the English-language Wikipedia than to any other website in the world, and Wikipedia predominates in knowledge panels, the information boxes that show up in Google searches, which are visible to users without scrolling.Footnote4 Multiple websites mirror Wikipedia’s content and students read it for their college papers; indeed, even judges rely on Wikipedia to rule on cases.Footnote5

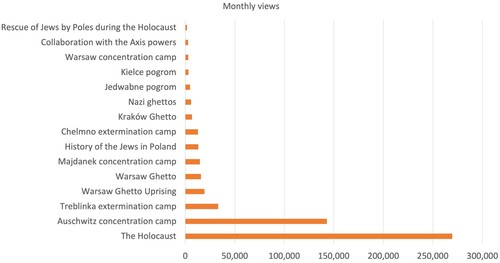

Wikipedia plays a critical role in informing the public about the Holocaust in Poland. The Wikipedia article ‘Holocaust’ tops the charts with an average of nearly 270,000 monthly views, but even more obscure articles, such as ‘Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust,’ receive as many as 1,700 views a month (Chart 1).Footnote6 This exposure surpasses that of any monograph or journal article, suggesting that Wikipedia shapes public knowledge about the Holocaust far more than scholarship does. Scholars have been aware of a problem in Wikipedia’s articles in this area for some years.Footnote7

Chart 1. Monthly views of Poland-focused articles relating to the Holocaust.

The misrepresentation of Polish–Jewish history is nothing new, and far predates the online encyclopedia or indeed the internet. For decades after the end of the war, the dominant approach in Poland held that most Poles were disgusted by German antisemitism, and that many risked their lives to save their Jewish neighbors. Research, especially from the last three decades, shows otherwise. Some Poles did help Jews, at great risk, but antisemitism existed among all swaths of Polish society, including the Polish underground, and anti-Jewish violence was a common occurrence.Footnote8

In the 1980s, some Catholic Poles began to concede on the point of their own society’s role in the persecution of Jews. ‘Yes, we are guilty,’ admitted the literary critic and professor of Polish literature Jan Błoński, in a groundbreaking piece in 1987, although even he was unable to admit that parts of Polish society had taken part in the German genocidal project.Footnote9 Soon, scholars of the Holocaust were to go far beyond Błoński’s conclusions. A rich body of scholarship emerged in the 2000s among Polish academics, with new studies on interwar antisemitism, postwar anti-Jewish violence – especially the notorious Kielce (1946) and Kraków (1945) pogroms – and on the Church’s connection with and involvement in anti-Jewish hostility.Footnote10 This scholarly drive came on the heels of the publication of Jan Gross’s seminal book, Neighbors (published in Polish in 2000) about the gruesome murder of the Jews of Jedwabne in the summer of 1941 by their Polish neighbors.Footnote11 The majority of non-Polish and Polish historians alike accepted the basic findings of Gross’s research, even if a healthy debate arose on the particulars.Footnote12 Since Gross, growing numbers of historians both in Poland and elsewhere have researched Polish–Jewish wartime relations, critically and dispassionately.Footnote13 One illustration of the Poles’ greater willingness to face its past was the government-appointed historical agency, the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN). In the early 2000s, the IPN temporarily embraced research on the most painful subjects of Polish–Jewish history.Footnote14

Gross’s work also led to a backlash among some Poles and Polish expatriates. For these people, Neighbors and its like appeared as defamatory attacks on the Polish nation. A number of Polish nationalists, among them politicians, journalists, and also some historians, preferred the comfort of old tropes. They completely rejected the dark chapters in Poland’s past, and instead emphasized Polish victimhood and heroism. These right-wing, nationalistic chroniclers of Poland’s past are often fringe academics – at least within the field of Holocaust history – and have been criticized by mainstream academia both in Poland and abroad for lacking empirical evidence.Footnote15 But in 2015, with the election of the right-wing Law and Justice party (PiS), they gained a dominant place. The state has tried to impose its view of history, for example by promoting museums featuring Polish suffering and emphasizing the role Poles played in saving Jews.Footnote16 The IPN, which had moved rightward even before PiS’s victory, now employs more than 2,500 well-paid professionals (including over 400 employees with doctoral diplomas) and a clear agenda of clearing Poland’s reputation.Footnote17 The majority of noteworthy historians of Polish–Jewish relations employed by the IPN, including Andrzej Żbikowski, Dariusz Libionka, Adam Puławski, and Krzysztof Persak, all quit or were fired,Footnote18 and in February 2021, testifying to the institutional culture of this organization, the IPN appointed Dr. Tomasz Greniuch to direct its Wrocław office. Greniuch has been photographed raising his right arm in the so-called Hitler salute (Hitlergruss) and was a member of the ONR (Obóz Narodowo-Radykalny, or the National-Radical Camp), which the Polish Supreme Court agreed ‘can be called a fascist organization.’Footnote19

The Polish government’s resolve to control the past culminated with the passage in 2018 of the Amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance, often dubbed the ‘Polish Holocaust Law.’ This legislation, amending a law which had been in place since 1998, penalizes those who ‘slander the good name of the Polish nation’ and who ‘blame the Polish society for crimes committed by the Nazi Third Reich.’Footnote20 The new law instilled an atmosphere of fear, as it not only delegitimized findings like Gross’s, but potentially exposed scholars, educators, teachers, and the reading public to civil and criminal charges. Furthermore, the law delegated to prosecutors the authority to decide what really happened in the past. Although the PiS’s efforts have had few legal ramifications – the handful of lawsuits waged by Polish agencies against ‘offending’ scholars or journalists failed in the face of lack of evidenceFootnote21 – the party has given confidence to far-right Poles both at home and abroad, with worrying consequences. Believers of these ethnonationalist claims are working hard to sway Anglophone public opinion, including through the English-language Wikipedia,Footnote22 the first place nonexperts go for information on most topics.

For the last few years, Wikipedia’s articles on the Holocaust in Poland have been shaped by a group of individuals (‘editors’ or ‘Wikipedians’ in Wiki parlance) with a Polish nationalist bent. Their Wikipedia names are Piotrus, Volunteer Marek, GizzyCatBella, Nihil novi, Lembit Staan, and Xx236, as well as previously active editors Poeticbent, MyMoloboaccount, Tatzref, Jacurek, and Halibutt.Footnote23 Combined, these individuals have authored substantial portions of multiple Wikipedia articles, both large (like ‘History of the Jews in Poland,’ where they have authored 67 percent) and small (like ‘Naliboki,’ where they are responsible for 70 percent – see Chart 2).Footnote24 Their massaging of the past ranges from minor errors to subtle manipulations and outright lies. In one glaring example authored by Halibutt, which reached the Israeli newspaper Haaretz in 2019, an entire Wikipedia article claimed for fifteen years that in a concentration camp in Warsaw, the Germans annihilated 200,000 non-Jewish Poles in a giant gas chamber.Footnote25Two editors named K.e.coffman and Icewhiz removed this falsehood,Footnote26 but other manipulations remain and more are added daily to the online encyclopedia.

Chart 2. Authorship of Wikipedia articles.

When distorting the past, the editors involved cite unreliable sources such as popular websites, self-published work, or academic work that has been widely discredited. At times they cite solid scholarship but misrepresent it to support their agenda. The same group of Wikipedians also wage a war of legitimacy on Holocaust historians themselves, inserting scathing critiques into Wikipedia biographies of mainstream scholars, and idealizing the biographies of fringe academics.

Holocaust envy, inflation of Polish rescue, and antisemitism

Four distortions dominate Wikipedia’s coverage of Polish–Jewish wartime history: a false equivalence narrative suggesting that Poles and Jews suffered equally in World War II; a false innocence narrative, arguing that Polish antisemitism was marginal, while the Poles’ role in saving Jews was monumental; antisemitic tropes insinuating that most Jews supported Communism and conspired with Communists to betray Poles (Żydokomuna or Judeo–Bolshevism), that money-hungry Jews controlled or still control Poland, and that Jews bear responsibility for their own persecution. Finally, distortionists inflate Jewish collaboration with the Nazis to make it seem an important part of the German policy of the extermination of European Jewry.

Poles as victims and heroes

One prominent example of editors warping the historical record appears in the Wikipedia article ‘Rescue of Jews by Poles During the Holocaust,’ which inflates the number of Polish victims and saviors.Footnote27 ‘Of the estimated 3 million non-Jewish Poles killed in World War II,’ claims the article, ‘thousands were executed by the Germans solely for saving Jews.’Footnote28 Both figures are false. The estimate of 3 million non-Jewish Polish victims of World War II was pulled out of thin air in 1946 by Jakub Berman, head of the Polish security apparatus, in order to establish Polish and Jewish losses on par.Footnote29 According to historian Gniazdowski, officials at the time presented ‘an equal proportion of losses among Poles and Jews, although according to the contemporary, and to subsequent estimates, Jewish losses were higher.’ Evidently, he explained, they were ‘fearful of issuing an official estimate which would indicate that Poles were ‘less impacted’ by war than the Jews.’Footnote30 It was one of the first examples of a phenomenon which historians today call ‘Holocaust envy.’Footnote31 In contrast, the 1945 official Polish estimates put the number of Polish victims of World War II at 1.8 million. The most recent estimates put the ethnic Polish losses at closer to 2 million, still well below the Wikipedia claim.Footnote32 Moreover, the number of Poles executed by the Germans solely for helping the Jews was not in the thousands, as the Wikipedia page claims. Research conducted in the 1980s and 1990s showed that the number of Polish victims killed for aiding Jews was closer to 800.Footnote33 More recently, historians reevaluated these estimates downward still.Footnote34

In order to shore up the argument about the alleged thousands of Poles killed for rescuing Jews, the Wikipedia article cites Richard C. Lukas’s 1989 book Out of the Inferno: Poles Remember the Holocaust, a book that has been heavily criticized by experts. Page thirteen of this book estimates that ‘a few thousand to fifty thousand’ Poles were killed by Germans for rescuing Jews. Yet, Out of the Inferno comprises little more than an anthology of short testimonies collected, edited, and introduced by Lukas. Page fifteen of his book says the following:

‘If the truth were known,’ said one of my Polish respondents, who was researching the subject at the time of his death, ‘the number of Jews hiding in Poland––most of them helped in some way by Gentiles––ran into the hundreds of thousands. Another informed estimate of the number of Jews sheltered by Poles at one point during the German occupation places the figure as high as 450,000.’Footnote35

We are asked to believe the estimate of one Jan Januszewski given to Lukas during an interview in 1982, yet no research substantiates it. Furthermore, the estimate of 450,000 Jews allegedly sheltered by the Poles is based on the writings of one Władysław Żarski-Zajdler, author of a propaganda brochure published in Poland in 1968, as part of that year’s government-sponsored antisemitic campaign. None of these figures are borne out by historical research. Wikipedia also downplays the scope and nature of Polish collaboration with the Germans. The Wikipedia article ‘Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust’ claims that ‘less than one tenth of 1 percent of native Poles collaborated, according to statistics of the Israeli War Crimes Commission.’ Historians have no way of making such an estimation, which depends on how one defines ‘collaboration.’ Some early work by the Israeli government estimated the number of people directly and institutionally engaged in organized killings, but the number of individuals who contributed indirectly to the Jewish catastrophe remains unknown.Footnote36 ‘The History of the Jews in Poland’ Wikipedia article similarly states, ‘Although the Holocaust occurred largely in German-occupied Poland, there was little collaboration with the Nazis by its citizens.’Footnote37 This claim has no footnote or truth to it; we know from voluminous research that betrayal of Jews by Poles was common.Footnote38

The Wikipedia article ‘Collaboration with the Axis powers’ provides still more errors of this sort. ‘Shortly after the German Invasion of Poland,’ says the article’s section on Poland, ‘the Nazi authorities ordered the mobilization of prewar Polish officials and the Polish police (the Blue Police), who were forced, under penalty of death, to work for the German occupation authorities.’ The Germans did indeed impose severe punishments on those refusing to serve in the new police force, but not the death penalty, and no documented case exists of a Polish officer being executed for such refusal. ‘While many officials and police reluctantly followed German orders,’ continues the article, ‘some acted as agents for the Polish resistance.’ This phrasing suggests Polish collaborators were at most reluctant, never willing; in fact, some police and civil administration officials served the Germans with zeal and devotion.Footnote39 The article claims that

the Polish Underground State’s wartime Underground courts investigated 17,000 Poles who collaborated with the Germans; about 3,500 were sentenced to death. Some of the collaborators––szmalcowniks––blackmailed Jews and their Polish rescuers and assisted the Germans as informers, turning in Jews and Poles who hid them, and reporting on the Polish resistance.

This excerpt implies that the Polish underground was preoccupied with penalizing the blackmailers of Jews. In reality, no more than seven out of thousands of the people involved in this activity were actually sentenced to death and executed, despite desperate pleas made by the Committee to Aid Jews (Żegota) to the underground decision-makers to pay more attention to fighting the szmalcowniks.Footnote40 Still more exaggerated Polish heroism appears in the article ‘Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust,’ which claims that ‘the Home Army (the Polish Resistance) alerted the world to the Holocaust through the reports of Polish Army officer Witold Pilecki, conveyed by Polish government-in-exile courier Jan Karski.’Footnote41 Nearly everything is wrong here. First of all, as we know today, the report regarding the destruction of Polish Jewry was delivered to the Polish authorities in London, not by Jan Karski (nowadays celebrated in film and popular literature), but by another courier.Footnote42 Second, Pilecki wrote his report in the summer of 1943, by which point the vast majority of Polish Jews had already been murdered, and Jan Karski, the courier, had left Poland in the fall of 1942. Karski (or any other courier) simply could not have carried abroad a report written nearly one year after his departure. Finally, Pilecki’s 1943 40-page report (the so-called Report W) described the situation at Auschwitz I main camp, but barely mentioned the ongoing extermination of Jews in nearby Auschwitz II–Birkenau and instead focused on the Polish camp resistance movement.Footnote43

In another instance of inflated claims about Polish aid toward Jews, the same article states (once again citing Lukas), ‘The imposition of the death penalty for Poles aiding Jews was unique to Poland among all German-occupied countries and was a result of the conspicuous and spontaneous nature of such an aid.’Footnote44 In fact, the death penalty did not apply specifically to Poles, but to all non-German inhabitants of the Generalgouvernement, including millions of Ukrainians, Belorussians, and other minorities living on prewar Polish territory. Moreover, the obvious explanation for the introduction of the death penalty for aiding and abetting the Jews was that Poland housed the majority of European Jews, and it was in Poland where the Germans decided to implement the ‘final solution of the Jewish question,’ namely, the physical extermination of European Jews. Furthermore, the death penalty was introduced in October 1941,Footnote45 long before any signs of ‘conspicuous and spontaneous help’ could have manifested themselves. Typical of the feel-good narrative commonly espoused by Polish nationalists, the Wikipedia article tells the story of the ‘Ulma family (father, mother and six children) of the village of Markowa near Łańcut … [who] were executed jointly by the Nazis with the eight Jews they hid.’ True, but these Poles hiding the Jews in Markowa were most afraid of their Polish neighbors who, in large numbers, conducted searches and manhunts for Jews in the village and in the area throughout the occupation. Furthermore, the Ulmas were denounced to the Germans by a Polish policeman. In such a way, most of Markowa’s Jews were delivered for execution to the Germans by their own Polish neighbors, some of whom continued to look for the Jews even after liberation.Footnote46 This entire context is tellingly absent from the discussed article.

In another attempt at reinforcing the heroic Polish narrative, the Wikipedia article states,

Nazi death squads carried out mass executions of entire villages that were discovered to be aiding Jews on a communal level. In the villages of Białka near Parczew and Sterdyń near Sokołów Podlaski, 150 villagers were massacred for sheltering Jews.Footnote47

Even more misleading claims appear in the Wikipedia article ‘Nazi crimes against the Polish nation,’ which says, ‘About 20,000 villagers, some of whom were burned alive, were murdered in large-scale punitive operations targeting rural settlements suspected of aiding the resistance or hiding Jews and other fugitives.’Footnote48 These statements distort and lie. Individual shootings were reported on numerous occasions, but never were entire village populations targeted for helping Jews. It is true that the Germans executed 96 men in the abovementioned village of Białka. It is not true, however, that this act of terror in any way stemmed from villagers helping Jews. The German crime was an act of reprisal for the assistance that the peasants were thought to have given to the local communist and left-wing partisans.Footnote49 The presence of these partisans (and there were some Jews among them) is well-documented in historical literature. It was only recently that attempts have been made, within the framework of the Polish ‘history policy,’ to link the mass shooting in Białka to the alleged help offered to Jews by the local population. The editors cite a 1988 work by Waclaw Zajączkowski entitled Martyrs of Charity, a blatantly hagiographical book, devoid of any academic standards, written to elevate Polish national heroism and suffering.Footnote50 Interestingly, the Polish Wikipedia entry for Białka correctly states that the villagers were executed for helping the partisans, while the English version erroneously claims that the execution resulted from local peasants helping the Jews.Footnote51

In another case of exaggerating Polish suffering and heroism, the Wikipedia article states,

after the end of the war Poles who saved Jews during the Nazi occupation very often became the victims of repression at the hands of the Communist security apparatus, due to their instinctive devotion to social justice which they saw as being abused by the government.Footnote52

This quote is credited to Jan Żaryn, a fervent nationalist, a darling of Polish right-wing populists, and the current chief of the newly established, government-funded Roman Dmowski Institute of National Thought (Dmowski was a prewar Polish politician, an unrepentant antisemite, and a great admirer of Adolf Hitler). Żaryn’s assertion is simply wrong. After the war, Polish rescuers of Jews were not afraid of communist authorities as much as they were afraid of right-wing anticommunist militias for whom rescuing the Jews was tantamount to national treason.z Examples of Polish rescuers killed or threatened by Polish nationalists surface in many Polish and Jewish accounts from the post-1944 period. Perhaps the best known is the case of Antonina Wyrzykowska from the Jedwabne area who managed to rescue a group of several Jews in her house. Soon after the liberation she and her husband were severely beaten by a group of Polish nationalists furious at her for having saved Jews. In a second case, righteous Jozefa Gibes (who saved a Jewish family of four) died soon after the war. Her body, lying in a coffin in the church, was sprayed with bullets by members of the underground as retribution for her help to the Jews.Footnote53 The list goes on of rescuers punished by either the anticommunist and antisemitic underground, or by Polish neighbors. Alfreda and Bolesław Pietraszek from Czekanów, Anna Wasilewska and her family from Zucielec, and the Danieluk family from Solniki, were all intimidated, wounded, or killed by the underground after the end of the war for having sheltered Jews under the Nazi occupation.Footnote54 A Polish rescuer of a Jewish infant shortly after the war wrote the following to the Central Committee of Polish Jews: ‘Two weeks ago, a band of native fascists broke into my house and smashed everything to pieces. They beat and kicked me and cut my wife’s and daughters’ hair, shouting: “that is for the Jewish child.”’Footnote55 Similar reports were filed from practically all areas of occupied Poland where significant numbers of Jews survived in hiding. Jan T. Gross summarized this situation in the following words:

The future Righteous’ wartime behavior broke the socially approved norm, demonstrating that they were different from everybody else, and therefore, a danger to the community. They were a threat to others because, potentially, they could bear witness. They could tell what had happened to local Jews because they were not––whether by their deeds or by their reluctance to act––bonded into a community of silence over this matter.Footnote56

The Wikipedia article ‘Polish Righteous Among the Nations’ echoes the same tropes of Polish heroism. ‘Many Polish Gentiles concealed hundreds of thousands of their Jewish neighbors,’ it states.Footnote57 Considering no more than 30,000 (out of more than 3 million) Polish Jews survived the war and occupation on Polish territory,Footnote58 and that many of these survived without Polish help, to argue that hundreds of thousands of Jews found shelter in Polish homes is nonsensical. Wikipedia’s reference is Tadeusz Piotrowski’s Poland’s Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947.Footnote59 This book, published in 1998, has received only two academic reviews, consists of little more than a collection of quotations taken out of context, and freely quotes Leszek Zebrowski, an economist by trade, known for his ultranationalistic views and spirited defense of prominent Polish antisemites.Footnote60 Piotrowski’s work attempts to convince the reader that Jews collaborated massively with the communists both during and after the war, that Jewish traitors and collaborators were one of the major reasons for the Jewish catastrophe, and that despite all of this, Poles did everything humanly possible to save their Jewish co-citizens. The rare demonstrations of Polish antisemitism, argues Piotrowski, stemmed directly from the attitudes and behavior of the Jews.

A historian will immediately recognize the statement on Poles hiding ‘hundreds of thousands’ as absurd, yet most readers of the ‘Polish Righteous Among the Nations’ page will not. Indeed, the page boasts ‘Good Article’ status, which means that it has been deemed ‘well written, contain[ing] factually accurate and verifiable information … [and] neutral in point of view.’Footnote61 The person nominating this article for Good Article status was an editor named Piotrus, on whom we will expand further in the essay.Footnote62

The theme of Polish innocence resurfaces in the Wikipedia article on the July 1946 Kielce pogrom. The deadliest pogrom in postwar Europe, this event claimed the lives of 42 Polish Jews, the majority Holocaust survivors, when a Polish mob enraged by tales of ritual murder attacked their neighbors. Misleadingly, over a fifth of the Wikipedia article comprises a subsection entitled ‘Evidence of Soviet Involvement,’ which suggests that the Kielce pogrom was somehow planned by the Soviets. This theory has been roundly rejected by all serious scholars and today finds an audience only among fringe Polish nationalists and conspiracy theorists wishing to prove that Communist Soviets, not Polish antisemitic masses, bore responsibility for the massacre. Tellingly, Joanna Tokarska-Bakir’s Pod Klątwą. Społeczny portret pogromu kieleckiego (Under the curse: the social portrait of the Kielce pogrom), winner of the 2019 Yad Vashem International Book Award, the definitive study which put the Soviet involvement thesis to rest, is completely absent from the Wikipedia article. Instead, readers again encounter references to Piotrowski’s Poland’s Holocaust.Footnote63

Jews as communists and collaborators Wikipedia’s coverage of Polish–Jewish relations contains both subtle and overt prejudices against Jews. Articles on the Holocaust and interwar years engage in victim blaming, suggesting Jews were at fault for antisemitism. Some statements hint that Jews are racially different from ethnic Poles, others argue that Jews refused to integrate into Polish society, and still others invoke an image of greedy Jews who enjoyed a plush life while ethnic Poles lived in poverty. Take the claim in the ‘History of the Jews in Poland’ article, that Jews have ‘specific physical characteristics.’ The citation for this sentence is a broken link to a website referencing Nechama Tec.Footnote64 Nechama Tec has said that the Germans used ‘the emotional argument that the Jews of Europe were not simply another ethnic minority, but rather a separate race, with separate and readily distinguishable values and, in particular, physical characteristics.’ Tec never said that Jews looked different, though. Indeed, she emphasized that ‘belying this myth was the fact that the Germans occupying Poland could not, by employing their own distinctions, separate Jew from Christian.’Footnote65 There were many stereotypes that Jews in hiding had to be aware of, but it is one thing to be aware of existing stereotypes and quite another to confirm their credibility, as the article seems to do.

Equally problematic in the same article is the sentence, ‘In many areas of the country, the majority of retail businesses were owned by Jews, who were sometimes among the wealthiest members of their communities.’ Since research on interwar Polish Jewry has shown that most Jews lived in poverty, this emphasis on Jewish wealth misleads readers.Footnote66 The citation to this claim is page 84 in a book by one Peter Stachura, but that page contains no such information.Footnote67 In its original version, inserted in 2008, the sentence had no citation whatsoever and was even more misleading: ‘some Jews were among the wealthiest citizens of Poland.’Footnote68 Past versions of the Wikipedia article ‘History of the Jews in Poland’ contained more distortions, such as the statement, introduced by an editor called Jacurek in 2007, that ‘Poland’s postwar Communist government was Jewish-dominated. Two out of three communist leaders who dominated Poland between 1948 and 1956 (Jakub Berman and Hilary Minc) were of Jewish origin.’Footnote69 Jacurek’s assertion is a typical example of antisemitic tropes being used by distortionists. Indeed, there were some people (a minority, obviously) of Jewish origin in the postwar communist apparatus in Poland. They were, however, most of all – as was clear in the case of Jakub Berman – loyal and ideologically engaged communists, for whom concepts of ethnic identity carried little weight when set against their class allegiance.Footnote70 Implying that politicians’ Jewish origins informed their political choices and decisions, or that they pursued an undefined ‘Jewish agenda,’ is one of the old antisemitic clichés that have been used to attack statesmen from Benjamin Disraeli to Léon Blum and beyond.

Multiple Wikipedia articles portray Jews as perpetrators, above all as keen collaborators with the Germans. In such a narrative, Poles faced threats from everyone, Jews included. ‘Polish rescuers [of Jews] faced threats from unsympathetic neighbors, the Polish-German Volksdeutsche, the ethnic Ukrainian pro-Nazis, as well as blackmailers called szmalcowniks, along with the Jewish collaborators from Zagiew and Group 13,’ states the article ‘Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust,’ adding, ‘The Catholic saviors of Jews were also betrayed under duress by the Jews in hiding following capture by the German Order Police battalions and the Gestapo, which resulted in the Nazi murder of the entire networks of Polish helpers.’Footnote71 In reality, the activities of the collaborationist Group 13 in the Warsaw ghetto (whose members had been arrested by the Germans in April 1942) had no bearing on the fate of Poles hiding the Jews after the liquidation of the ghettos. The Wikipedia editors once again cite Zajączkowski’s pious hagiography Martyrs of Charity and place blame for the Holocaust on the shoulders of the victims, a form of denial and distortion which recurs frequently nowadays in the writings of Polish nationalists associated with the IPN.

Wikipedia articles repeatedly inflate and distort the phenomenon of Jewish collaborators. In the article ‘Collaboration with the Axis powers,’ over a quarter of the section on Poland covers the Jewish Councils, the Judenräte, wrongly casting them predominantly as German collaborators. The article states,

The Germans set up Jewish-run governing bodies in Jewish communities and ghettos––Judenrat (Jewish council) that served as self-enforcing intermediaries for managing Jewish communities and ghettos; and Jewish Ghetto Police (Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst), which functioned as auxiliary police forces tasked with maintaining order and combating crime … . Additionally, Jewish collaborationist groups such as Żagiew and Group 13 worked directly for the German Gestapo, informing on Polish resistance efforts to save Jews.

Jewish council members were hardly ‘self-enforcing intermediaries for managing Jewish communities.’ They were tightly supervised by the German police (Schupo, Orpo, Gestapo, to name but a few), the Polish police, and German civil administrators, while the Jewish police were closely supervised by the Polish Blue Police. Judenrat members who failed to comply usually faced imprisonment and death, and most Jewish policemen were murdered only shortly after the other Jews in their local community. Placing those people on equal footing with Polish policemen and administrators, who had a real choice, who could kill, and who could refuse to kill with impunity, gravely distorts history.Footnote72 Similar problems plague the article ‘Collaboration in German-Occupied Poland,’ where alleged Jewish collaboration with the Nazis takes up more space than the Ukrainian, Belorussian, and ethnic German collaboration combined. ‘Jews helped the Germans in return for limited freedom, safety and other compensation (food, money) for the collaborators and their relatives,’ the article posits. ‘Some were motivated purely by self-interest, such as individual survival, revenge, or greed; others were coerced into collaborating with the Germans.’ The editors writing these sentences seem to forget that Jewish collaborators were, above all, victims and hostages of a choiceless choice. They became ‘forced traitors,’ to use Doris Tausendfreund’s expression, in order to preserve their own lives, or the lives of their loved ones.Footnote73

More dubious claims follow, such as ‘In Warsaw, the collaborationist groups Zagiew and Group 13, led by Abraham Gancwajch and colloquially known as the ‘Jewish Gestapo,’ inflicted considerable damage on both Jewish and Polish underground resistance movements.’ Gancwajch did indeed serve as a Jewish collaborator in the Warsaw ghetto, but no evidence suggests he inflicted any damage on the Polish underground. The source of this statement, Henryk Piecuch, is not an academic but a former employee of the Polish communist Ministry of Interior, without any historical training. Given that he lacks any expertise on wartime Jewish–Polish history and provides no evidence of any work in the archives, quoting him as an authority on these topics is illogical. The article further claims that ‘over a thousand such Jewish Nazi collaborators, some armed with firearms, served under the German Gestapo as informers on Polish resistance efforts to hide Jews’ and that ‘at the end of 1941 and the start of 1942 there were some 15,000 ‘Jewish Gestapo’ agents in the General Government.’ These figures, attributed to Piecuch and Piotrowski, are blatantly false. The article’s assertion that the Zagiew network used Hotel Polski to entrap ‘2,500 Jews … [who were then] captured by the Germans’ also strays from the truth. The Hotel Polski affair was not initiated by Jewish collaborators (although some, like the notorious Lolek Skosowski, were involved), rather it was planned by the Warsaw Gestapo. Indeed, the plan aimed to create a place for exchanging Jews for German prisoners of war held by the Allies. Although most of the Jews who went through Hotel Polski died, several hundred others were sent abroad, exchanged, and continued on to Palestine, surviving the war.Footnote74

The same article also talks about

a 70-strong group led by a Jewish collaborator called Hening [which] was tasked with operating against the Polish resistance, and was quartered at the Gestapo’s Warsaw headquarters on ulica Szucha (Szuch Street [sic]). Similar groups and individuals operated in towns and cities across German-occupied Poland––including Józef Diamand [sic] in Kraków.

The alleged group led by Hening is unknown to historians of Warsaw Jewry and Wikipedia’s author for this claim is, once again, Tadeusz Piotrowski. Meanwhile, the alleged group of Jewish collaborators led by Józef Diamant in Kraków is a fabrication exposed by Kraków-based historian Alicja Jarkowska-Natkaniec. In her study, she not only debunks claims regarding Diamant, but she also shows that most of the Polish underground fighters denounced in Kraków to the Germans were turned in by ethnic Poles.Footnote75

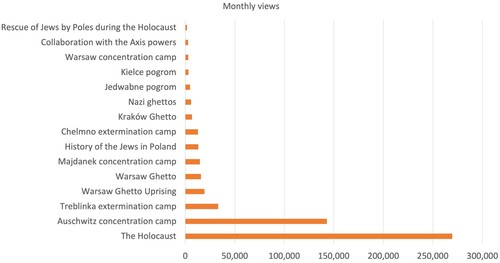

The charge of Żydokomuna, that Jews were in the majority communist or conspired with the communists to hurt Poles, occurs frequently on Wikipedia. One vivid example of this form of antisemitism was made by an editor called Poeticbent, in real life Richard Tylman, a Polish–Canadian poet, and painter.Footnote76 In 2015, Poeticbent inserted into Wikipedia an image (Figure 1) showing a poster written in Yiddish, placed just beneath a hammer and sickle sign in Soviet-occupied Białystok. Poeticbent captioned it, ‘Jewish welcoming banner for the Soviet forces invading Poland.’Footnote77 In fact, this image showed nothing of the sort. The poster actually read, ‘Election of delegates for Western Belorussia People’s Assembly,’ meaning this was a Soviet sign advertising Soviet-imposed elections. The Soviets’ choice of Yiddish reflected this language’s importance in Białystok, where Jews, most of whom spoke Yiddish, comprised over 40 percent of the population.Footnote78 Poeticbent’s false caption, combined with the photograph’s particular composition – Hebrew letters directly under the USSR’s emblem – bolster the entrenched stereotype identifying Jews with communism. Furthermore, in a country brutally occupied by the Soviets, Poeticbent’s edit painted Jews as perpetrators. The image remained in Wikipedia, wrongly captioned, until 2018, when the editor Icewhiz corrected its description.Footnote79

Figure 1. Photograph of a sign in Białystok, wrongly captioned by Poeticbent as a Jewish welcoming banner for the Soviets.

Another form of antisemitism in Wikipedia’s coverage of World War II in Poland comprises fantastical accusations of Jews as perpetrators of wide-scale crimes. In March 2011, in an article about the northeastern Polish town of Stawiski, Poeticbent wrote that

Upon the Soviet invasion of eastern Poland in 1939, the local administration was abolished by the NKWD [National Commissariat for Internal Affairs, the Soviet secret police] and replaced with Jewish communists who declared Soviet allegiance. Ethnic Polish families were being rounded up by newly formed Jewish militia, and deported to Siberia.Footnote80

The footnote referred to scholarly works by Alexander Rossino, Dov Levin, and Yitzhak Arad, but a review of these texts reveals that not a single one contains information on Jewish militiamen in Stawiski.Footnote81 Poeticbent also downplayed Polish violence toward Jews, writing that the Poles who killed their Jewish neighbors did not do so of their own accord but ‘were led to acts of revenge killing in their [the Germans’] presence.’Footnote82 This last claim had no footnote at all. An almost identical falsification occurred in the Wikipedia article on the nearby town of Radziłów, where Poeticbent wrote that ‘Soviet-armed Jewish militiamen helped NKVD agents send Polish families into exile.’Footnote83 Another accusation of Jews killing Poles surfaces in the Wikipedia article ‘Naliboki massacre,’ which chronicles the killing of 129 Poles by Soviet partisans in May 1943 in Naliboki, a small town in western Belarus. The article insinuates that Jews, specifically the Soviet–Jewish Bielski partisan formation, took part in this massacre. We learn that the partisans numbered ‘Jews in their ranks,’ that ‘25% of the partisans were Jewish,’ that ‘the Bielski partisans … might have supported the Soviets in the attack based on their ongoing relationship,’ and that ‘surviving eyewitnesses from Naliboki recognized Jews who had previously been in the Bielski partisans participating in the attack.’Footnote84 A previous version of this article was even more explicit in blaming Jews for this atrocity, defining the massacre as ‘the mass killing of 128 Poles, including boys, by Soviet and Jewish partisans.’Footnote85 As a reference, an anonymous editor provided a photograph from the Los Angeles Museum of Tolerance showing Soviet–Jewish partisans in the Naliboki Forest.Footnote86 In fact, however, the photograph, undated, bears no evident relation to the massacre. Another source backing these statements, inserted by Poeticbent, is an article by Kazimierz Krajewski in an IPN bulletin.Footnote87 Quoting recent IPN publications destined for broad audiences in the context of Jewish–Polish history during the Holocaust is a risky endeavor and requires great vigilance and prudence, and Krajewski, who writes for the Polish far-right press, lacks broader expertise in Jewish–Polish issues.Footnote88

Wikipedia’s insinuation that Jews played a key role in perpetuating this massacre echoes distortions popular among right-wing fringe groups. It began in the early 2000s when the Toronto Branch of the Canadian Polish Congress (KPK), a right-wing group of Polish Canadians, alleged that in Naliboki and Koniuchy (a village in Lithuania), ‘Jewish partisans boast[ed] of killing 300 and 130 Poles respectively.’Footnote89 In 2001 the IPN launched an investigation into these two supposedly Jewish-led massacres at the request of the Canadian Polish Congress.Footnote90 Finding nothing, the IPN dismissed the claim years later, stating in 2008 that ‘several witnesses testify that there were partisans from Bielski among the attackers,’ but that ‘these statements are not supported by any other evidence, such as archival documents.’Footnote91 Wikipedia’s coverage of the Naliboki massacre should not even mention Jews; yet Jews occupy a third of the article. Various editors over the years tried to fix these edits, but they were brought back by Piotrus and by his like-minded colleague, Volunteer Marek.Footnote92

The same Wikipedians who distort the historical record also lend a hand in whitewashing current manifestations of Polish antisemitism. This is evident in the Wikipedia article ‘Jew with a Coin,’ which describes the recent phenomenon of Poles collecting miniatures and paintings of ‘Jewish-looking’ figures holding money. This kind of artwork features a male character with a beard, dressed in Hasidic clothing, often large-nosed and dark-skinned, and clutching gold coins (Figure 2). In a country where most real Jews were murdered, some precisely because of the stereotype of money-hungry Jews, such objects evoke clear antisemitic stereotypes.Footnote93 Anthropologist Erica Lehrer wrote about this phenomenon in Kazimierz (a center of Jewish life in Kraków) in her 2013 book Jewish Poland Revisited, uncovering that some Poles collect these odd pieces of art as good luck charms and may not consciously attribute sinister meaning to them.Footnote94 Yet, since her book’s publication, the figurines have turned into a mass trend, making it harder to disavow their antisemitic dimension.Footnote95 More recent scholarship has pointed out that the figurine phenomenon ‘seems at first glance to be neutral or even positive disposition but altogether continues and enshrines the well trodden path of anti-Jewish sentiment.’Footnote96 Sensitive to the offensive nature of these objects, the Polish OBI retail chain stopped offering ‘Jew with a coin’ art in its supermarkets, and Kraków’s municipal council, backed by the Jewish community and cultural institutions, issued a public statement against their sale.Footnote97

Figure 2. ‘Jew with a coin’ figurine from Wikipedia article.

On Wikipedia, this disturbing phenomenon is transformed into quaint artwork, thanks to the distortionist editors. A reader stumbling on Wikipedia’s take on ‘Jew with a Coin’ might even mistake this phenomenon for a pro-Jewish portrayal. The article’s very first paragraph states, ‘The Jew with a coin … is a good luck charm in Poland, where images or figurines of the character, usually accompanied by a proverb, are said to bring good fortune, particularly financially. For most Poles the figurines represent a harmless superstition and a positive, sympathetic portrayal of Jewishness.’Footnote98 In one short paragraph, the editors whitewash a clear manifestation of one of the most harmful anti-Jewish prejudices in existence; the association of Jews with money or greed. For a time the article used the phrase ‘controversial good luck charm,’ at least hinting at the figurines’ pernicious character, but Piotrus struck ‘controversial’ from the sentence.Footnote99 A 2015 survey of over 500 adult Poles found that a staggering nineteen percent owned a ‘Jew with a coin,’ while 55 percent had seen one at a friend’s or family member’s house.Footnote100 But a Wikipedia editor called MyMoloboaccount, also one of the group, changed the optics of this figure by saying that ‘only 19% of surveyed Poles owned such an item’ (emphasis added by authors). MyMoloboaccount and Piotrus together edited the article to say that ‘the figurines are not the most popular good luck charm in Poland.’Footnote101 Not for nothing did the two focus their energies on this opening section of the article, called the ‘lead,’ as readers of Wikipedia often read only that.Footnote102

Unreliable sourcing

In theory, Wikipedia’s policy on sourcing serves as a safeguard against editors who falsify information. The site requires that ‘articles should be based on reliable, published sources,’Footnote103 disqualifying data from unreliable sources. In most areas of the encyclopedia, this provision serves its function: if an editor comes across an unreliable source, they can remove it, and if another Wikipedian repeatedly restores it, administrators (editors with special privileges) can impose sanctions against the offending party. However, the distortionist editors in the area of Holocaust history in Poland abuse this system by contesting the very definition of reliable research. They spend a considerable amount of time legitimizing nonacademic sources and authors, and, conversely, delegitimizing trustworthy works and authors. So, when uninvolved editors or administrators arrive to settle an editing conflict, they have a hard time telling right from wrong.

Legitimizing fringe academics

Take The Forgotten Holocaust, a 1986 book by the aforementioned Richard C. Lukas that borders on Holocaust distortion. Lukas attempted, without any reference to historical evidence from the Polish, Israeli, or German archives, to broaden the definition of the Holocaust in such a way as to also include the killings of ethnic Poles by the Germans. As soon as The Forgotten Holocaust came out, David Engel, one of the most eminent historians of the Holocaust, wrote a thirteen-page scathing critique of the book in the journal Slavic Review, where he charged Lukas’s research with ‘distortion, misrepresentation and inaccuracy.’Footnote104 Engel demonstrated in detail that Lukas had made sweeping generalizations, invented facts, disregarded archival sources, and displayed a complete lack of familiarity with secondary sources.

Despite Lukas’s clear weaknesses, the editor Piotrus has written him a glowing Wikipedia biography.Footnote105 Piotrus trivializes Engel’s critique by juxtaposing it with multiple enthusiastic appraisals of The Forgotten Holocaust. ‘It has received a number of positive reviews, and a single dissenting critical review,’ wrote Piotrus in Richard C. Lukas’s biography on Wikipedia.Footnote106 Indeed, Piotrus created a new article dedicated solely to The Forgotten Holocaust, where he quoted from the positive reviews in detail. A close look reveals that the laudatory evaluations were written by scholars with far less expertise on the topic than Engel (one of them was a graduate student who never went on to publish in the field; several others were not historians), and most were only one or two pages long. By portraying Engel’s opinion as a lone dissenter in a sea of praise, Piotrus massaged the Wikipedia article to show Lukas in a positive light. Another editor called François Robere tried to temper the article’s praise for Lukas, but Piotrus reverted him immediately.Footnote107 With 92 percent of the page’s content authored by Piotrus, Wikipedia’s article on The Forgotten Holocaust continues to celebrate Lukas.Footnote108

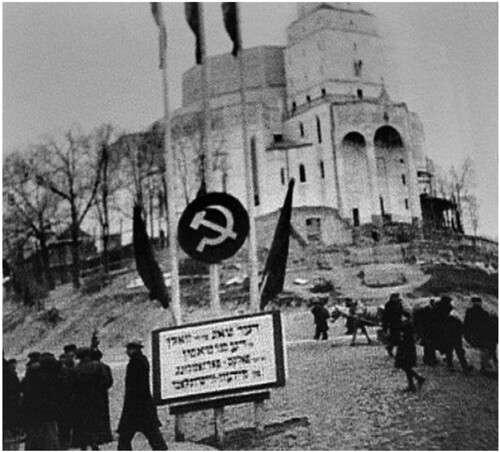

The positive biography on Wikipedia enables Piotrus and his colleagues to cite Lukas freely, and so they do. Wikipedia mentions Richard C. Lukas 82 times, more than it mentions Nechama Tec, Samuel Kassow, Doris Bergen, Deborah Dwork, or Zvi Gitelman, to name some well-known experts on Holocaust history. It is telling that the volume of Lukas’s citations on Wikipedia is inverse to the volume of citations he enjoys on Google Scholar, a more objective measure of reliability (Chart 3).Footnote109

Chart 3. Visibility on Wikipedia vs. on Google Scholar.

In another example of legitimizing weak sources, the distortionist group has extolled the historian Marek Jan Chodakiewicz. Chodakiewicz’s 2003 book, After the Holocaust, engaged in copious victim blaming, stating, ‘violence against Jews stemmed from a variety of Polish responses to at least three distinct phenomena: the actions of Jewish Communists … ; the deeds of Jewish avengers … ; and the efforts of the bulk of the members of the Jewish community, who attempted to reclaim their property … ’Footnote110 Chodakiewicz’s 2004 book, Between Nazis and Soviets, similarly held Jews responsible for Polish animosity toward them, stating that ‘Jewish fugitives had alienated much of the majority population by robbing food and necessities to survive,’ and that ‘between 1942 and 1944, Jewish supply raids and not Polish antisemitism ultimately determined the nature of mutual relations.’Footnote111 This type of writing garnered scathing critiques from experts in the field, including David Engel, who wrote that Chodakiewicz’s work implies that ‘the large majority of the Jews who died brought their deaths upon themselves through their own actions’ and that Chodakiewicz ‘represent[ed] the violence as almost entirely a rejoinder to provocative behavior by the Jews.’Footnote112 Joanna Michlic described Chodakiewicz’s work as ‘the most extreme spectrum in what is considered the contemporary mainstream ethnonationalist school of history writing.’ She explained that he ‘consistently casts Polish–Jewish relations in terms of conflict and uses conflict as an explanation and justification of anti-Jewish violence in modern Poland,’ and that this interpretation ‘neutralize[s] anti-Jewish violence by making it ‘guilt free.’’Footnote113 Laurence Weinbaum shared this critique, writing, ‘Chodakiewicz and like-minded historians seem reluctant to forgive the Jews for Jedwabne and the Kielce pogrom, and are hard at work explaining why the murdered—not the murderers—are guilty.’Footnote114

Chodakiewicz’s edited 2012 book Golden Harvest or Hearts of Gold, a crusade against Jan Gross’s book Golden Harvest from earlier that year, echoed the same tropes.Footnote115 While Gross’s book was published by Oxford University Press and won the Sybil Halpern Milton Book Prize, Chodakiewicz’s volume was published by Leopolis, a press run by Chodakiewicz himself.Footnote116 It therefore completely flouted academic publishing standards requiring rigorous and blind peer-review, and of its fourteen authors, only seven had PhDs, only two were faculty at universities (two more worked at the IPN), and one – Mark Paul, on whom we shall expand further on in this essay – maintained anonymity through a pseudonym. Riddled with grammatical errors, Golden Harvest or Hearts of Gold exaggerated Jewish profiteering and collaborationism, downplayed Polish antisemitism, and smeared not only Gross but other prominent historians, such as Piotr Wróbel and John Connelly.Footnote117 In his essay, the pseudonymous ‘Mark Paul’ dismisses the Grodno pogrom of September 17, 1939, in which close to thirty Jews were murdered by the Polish troops,Footnote118 saying, ‘Armed Jews held secret meetings in various areas of Grodno. Jadwiga Dąbrowska witnessed an assault and murder of her neighbor’s son, a Polish soldier, killed by a young Jewish participant in such a secret meeting.’Footnote119 Another essay, by Barbara Gorczycka-Muszyńska, argues – against overwhelming evidence – that the Jews returning to Poland after 1945 were privileged in reclaiming their property. Experts on this topic, in contrast, have shown beyond doubt that the entire administrative and judiciary system in 1945–1947 facilitated the final and legal transfer of ‘post-Jewish property’ (which, after 1942, had been largely taken over by the Polish neighbors) into the hands of ethnic Poles.Footnote120 In his introduction to the volume, Chodakiewicz writes about ‘Jewish gangs pulling out gold teeth from the victims at KL [concentration camp] Sachsenhausen, stealing part of the loot for themselves, later enriching the ‘chiefs of this enterprise’ – the SS guards.’Footnote121

Chodakiewicz’s dislike of minorities extends beyond Jews. In line with European right-wing nationalists who regard the LGBTQ + community as a threat to family and nation,Footnote122 Chodakiewicz has gone on record with blatantly homophobic remarks. ‘Nothing offends God more than throwing semen into the feces,’ he stated at an IPN event (available to watch on YouTube) held in Warsaw, in July 2019, and went on to claim that his ex-girlfriend, a nurse, once pulled a hamster out of a man’s rectum.Footnote123 Chodakiewicz’s book Intermarium (published by Routledge in 2012) provides a glimpse of his views. He describes ‘homosexual frolic’ and ‘so-called ‘gay pride’ parades’ as manifestations of ‘the EU’s radicalism,’ and commends countries who ‘lead the way’ with anti-LGBTQ + policies.Footnote124 Chodakiewicz’s homophobic comments dovetail with the official narrative of the Polish authorities which, since 2020, have been actively involved in attacking the LGBTQ + community.Footnote125

Despite editors repeatedly raising concerns about Chodakiewicz, the distortionist group has adamantly defended using his work as a valid source for Wikipedia content. When confronted with the fact that Golden Harvest or Hearts of Gold bordered on self-publication, Piotrus feebly protested, ‘it’s … still [an] academic press,’ ‘the essays seem to be well referenced,’ ‘no ‘red flags’ have been identified in the text, i.e. it makes no outlandish claims,’ and ‘it’s a reliable source that can be cited.’ Volunteer Marek gave even less of a justification, simply claiming that the volume was ‘an academic source and easily qualifies for reliability’ and adding, for good measure, ‘the notion that it’s not reliable is ridiculous.’Footnote126 In 2018, several editors added a number of scathing reviews of Chodakiewicz’s work to his Wikipedia biography, not before ensuring that these abided by Wikipedia’s policies on ‘Biographies of Living Persons’ (BLP in Wiki parlance), which requires that criticism of living persons relies on trustworthy sources, takes a conservative and a disinterested tone, and does not represent the views of small minorities.Footnote127 Volunteer Marek deleted them wholesale, citing in his edit summaries (a brief explanation editors need to give for changes they make) ‘this article [is] full of BLP vios [violations]’ and ‘stop trying to turn Wikipedia articles into attack pages on authors whom you disagree with.’Footnote128

Chodakiewicz’s work continues to be cited freely and frequently on Wikipedia. Although enough uninvolved editors weighed in to oppose citing Golden Harvest or Hearts of Gold,Footnote129 his other publications proliferate on Wikipedia far more than works by mainstream scholars. Like Lukas, his numerous mentions on Wikipedia (119 times)Footnote130 bear no relation to his modest visibility outside of the online encyclopedia (Chart 3).

Ewa Kurek provides yet a third example of an unreliable author favored by nationalist-leaning editors. Kurek has made disturbing antisemitic statements, recently describing the spread of COVID-19 in Europe as ‘Jewfication.’Footnote131 She is a Holocaust revisionist, as evident from the following excerpt from her recent online publication, Trudne sąsiedztwo: Polacy i Żydzi ok. 1000–1945 (Difficult Coexistence: Poles and Jews, 1000–1945). ‘In 1939–1942 the ‘goy’ (or Polish) Warsaw was a sad place,’ she wrote the following:

The [Polish] population was terrorized with constant German roundups, executions and deportations to concentration camps. During the same years the Jewish Autonomous Area, the Warsaw ghetto, lived it up. In 1941 Carnival season, in the Warsaw ghetto: in ‘Melody Palace’ they held a carnival dance featuring a “most beautiful legs” competition. Ghetto dances. Despite the fact that the carnival season is over, in the ghetto they open more and more night bars. On the other [Polish] side [of the wall] people say: “he enjoys himself as if he were in the ghetto.” Jewish policemen (who are not drawing any salaries) fill the most elegant venues, in the company of beautiful women. They set the tone for the night entertainment. Their elegant, shining officers’ boots must have impressed the ladies. A sort of high point of the life in the Jewish Autonomous Area in Warsaw was the introduction of work-free Saturday (replacing Sunday), as a Jewish day of rest.Footnote132

This ‘Jewish Autonomous Area,’ to use Kurek’s twisted expression for the Warsaw ghetto (the largest ghetto in Nazi-occupied Europe), was an area in which, in the spring, summer, and fall of 1941, 5,000 people per month starved to death.Footnote133 Given such blatant falsifications, some in the Wikipedia community reasonably called to reject Kurek as a reliable source, but the distortionist editors came to her defense. In 2018, the editor Icewhiz asked on Wikipedia’s Reliable Sources Noticeboard (a space for editors to discuss a source’s quality) to have Kurek’s work removed from a Wikipedia article. Icewhiz not only pointed out that it was self-published but informed the community about Kurek’s absurd claims that Jews enjoyed living in the ghettos. Piotrus pushed back. ‘I don’t think she is too unreliable to be cited for uncontroversial facts,’ he stated, leaving it up to editors to decide what qualified as ‘controversial.’ He added that ‘not every work about Jews in WWII has to focus on their suffering,’ and that ‘calling her an anti-Semite [sic] because she writes about other aspects of Jewish life is IMHO [in my humble opinion] unreasonable.’ Tatzref, an editor frequently allied with Piotrus, expressed indignation at the very idea of questioning Kurek. ‘So Kurek is a self-published amateur historian??? Does anyone actually do some genuine checking[?]’ he exclaimed, his confident tone suggesting that nobody in their right mind would discredit her.Footnote134 Volunteer Marek described Kurek as a ‘mainstream scholar,’Footnote135 while GizzyCatBella inserted her work into more than one article.Footnote136

Despite Kurek’s growing reputation as a Holocaust denier, in August 2021 an editor called Nihil novi once again inserted Kurek into Wikipedia, this time in an article on Jedwabne. The Jedwabne massacre, in which masses of Polish Jews were murdered by Poles on July 10, 1941, has been a sore point for Polish nationalists ever since the publication of Jan T. Gross’s book Neighbors, which chronicled the mass-murder. Nihil novi presented Kurek as an expert who both rejected the thesis that Poles killed Jews and challenged the high number of victims. ‘Kurek … speaks of absurdities in some accounts of the Jedwabne massacre,’ wrote Nihil novi, ‘such as that Poles shot at the Jews.’ Quoting Kurek, he continued,

the Germans would never have let the Poles use firearms […]. Until there is [a complete] exhumation, it will not be known how many Jews died. Some say 1,600, others 400, still others give different numbers. [S]eeking the perpetrator [before] the body [has been found] is both a legal and a historical absurdity. [Before] we do an exhumation [it will not be known] how many persons died and whether the Jews had been burned [alive] or first shot.Footnote137

Kurek’s assertions are gross falsifications. The Germans did indeed arm Polish peasants in order to create viable ‘night guards,’ self-protection units which were established across the occupied Generalgouvernement. Usually, the Germans provided the villagers with one to two rifles per village. More importantly, however, there is no evidence of any Jews having been killed with bullets on July 10, 1941. An exhaustive investigation conducted by the IPN itself from 2001 to 2004 (when the IPN still employed noteworthy scholars of Polish–Jewish relations) established beyond any reasonable doubt that the Jewish victims were burned alive in the barn, with many others killed by Poles in the streets and in the houses of Jedwabne.Footnote138 It is true that we shall probably never know the precise number of Jewish victims but that has no impact whatsoever on our understanding of the event. What is known, is that on July 10, 1941, the Polish inhabitants of the town of Jedwabne murdered all the Jewish neighbors they managed to locate.Footnote139 By displaying Kurek’s claims uncritically (presenting her neutrally as ‘Polish historian Ewa Kurek’), Nihil novi distorted history too, in an article that receives 62,000 views a month.Footnote140

Alongside Lukas, Chodakiewicz, and Kurek, the nationalist-leaning editors also favor citing Glaukopis, a journal which caters to, and is led by, the Polish extreme nationalistic right. Its long-time editor-in-chief, Wojciech Muszyński (an employee of the IPN), openly praises the ONR, one of the most militant, rabidly antisemitic organizations of prewar Poland.Footnote141 In an interview given to the right-wing paper Nasz Dziennik, Muszyński, referring to the vicious 1968 antisemitic campaign orchestrated by the communist authorities, falsely claimed that ‘it allowed Judeopoles [a term for Jews who pretend to be Poles] with secret-police and communist party-activist roots, to escape responsibility for their committed crimes.’Footnote142 On Glaukopis, Muszyński advanced the aforementioned groundless claim that Germans in the Warsaw concentration camp KL Warschau installed gas chambers in which ‘mostly Poles from Warsaw were murdered.’Footnote143 Glaukopis’s authors include the aforementioned Leszek Żebrowski,Footnote144 as well as Mariusz Bechta (from the IPN),Footnote145 who has published a long list of books by fascist authors. Among these books we find Leon Degrelle’s (Hitler’s favorite Belgian Nazi)Appeal to Young Europeans; a translation of Rivolta contro il mondo moderno by the Italian fascist Julius Evola; a manifesto by Jan Mosdorf, the fascist leader of the ONR; a book by Grzegorz Bębnik, ‘Ostatnia walka Afrykanerów’ (The Last Struggle of the Afrikaaners), which praises the struggles of the white minority in South Africa; and many more publications of the same ilk.Footnote146 Indeed, Bechta is also a vocal admirer of Janusz Waluś (the Polish-born killer of anti-apartheid leader Chris Hani in South Africa) and a former distributor of neo-Nazi music. In 2018, on the 77th anniversary of the German attack against the Soviet Union, Bechta posted on the fan page of Templum Novum (a journal published by Bechta himself) a poster calling for solidarity with the Nazis.Footnote147

Not surprisingly, Glaukopis caught the attention of a responsible Wikipedia editor. In February 2021, an editor called Buidhe challenged Glaukopis’s reliability on Wikipedia’s Reliable Sources Noticeboard. Glaukopis, Buidhe pointed out, was described by established historian Andrzej Żbikowski as ‘a publication that has arisen mainly to rehabilitate unconditionally the wartime activities of the Narodowe Siły Zbrojne (NSZ).’ Seeing as the NSZ was the military wing of Polish extreme nationalists, one of whose units, the Holy Cross Brigade, signed a truce with the Nazis, fought against Soviet forces and left-wing partisans, and murdered Jews, Buidhe rightly noted that Glaukopis was simply not a reliable source to use. The nationalist group on Wikipedia responded with a fierce defense of Glaukopis. It was reliable, claimed MyMoloboaccount, adding, ‘Peer reviewed, includes notable cited historians, involved with notable scholarly debates.’ Volunteer Marek agreed that ‘this [journal] shouldn’t be a concern,’ and GizzyCatBella wrote that ‘Glaukopis is an obvious peer-reviewed scholarly publication.’Footnote148 Outnumbered, Buidhe lost this debate and Glaukopis remained a permitted source on Wikipedia. Indeed, the nationalist-leaning group uses it to justify other unreliable sources, as in the case of Piotrus embellishing Ewa Kurek’s Wikipedia biography.Footnote149

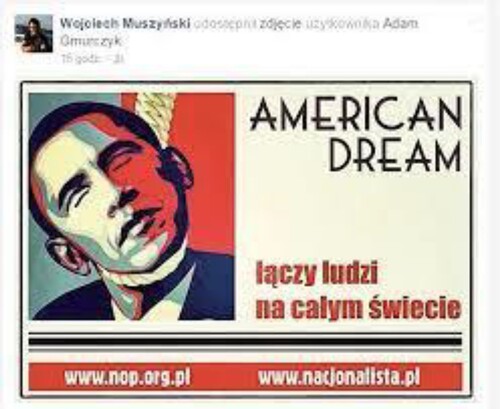

In their effort to argue for Glaukopis’s reliability, the distortionist group whitewashed the Wikipedia biography of its editor-in-chief, Muszyński. This man gained notoriety in 2015 for posting on his Facebook page a drawing of Barack Obama with a noose around his neck (Figure 3),Footnote150 and once again in 2019 for writing on his Facebook page that members of the left-leaning Polish Razem party should be, following the example from Pinochet’s Chile, ‘brought in helicopters over the ocean and thrown out there, 30 kilometers from the shore.’Footnote151 In September 2020 and February 2021, Buidhe and a user called Jacinda01 added these facts to Muszyński’s Wikipedia biography, using the mainstream Polish newspapers OKO Press and Gazeta Wyborcza as their sources. Yet Volunteer Marek, evidently intent on clearing Muszyński’s reputation, deleted them, dismissing OKO Press and Gazeta Wyborcza as unreliable sources.Footnote152 Even when it was pointed out in the Reliable Sources Noticeboard that The Washington Post considered Gazeta Wyborcza ‘Poland’s most popular and respected newspaper’ and that OKO Press received a Freedom of Expression Award from the British organization Index on Censorship, Volunteer Marek and GizzyCatBella claimed both outlets were ‘hyper partisan outlets’ and ‘NOT reliable.’Footnote153 For several months, the two kept deleting other editors’ attempts to bring Muszyński’s racist and violent pronouncements into the biography.Footnote154 It was only after the fourth attempt by other editors to include the paragraphs on Obama and Razem that GizzyCatBella and Volunteer Marek finally stood down.Footnote155 Still, Muszyński’s biography, over 50 percent of which is authored by Piotrus,Footnote156 continues to read as a list of accolades. While GizzyCatBella and Volunteer Marek guard that page, few editors are likely to attempt any major changes, or participate in discussion of sources.

Figure 3. An image from Wojciech Muszyński’s Facebook page in 2015, showing Obama’s head in a noose.

Another absurd source legitimized by the distortionist group is Mark Paul. This author appears to be a legitimate historian at first glance, with relevant publications in Holocaust history. In fact, ‘Mark Paul’ does not exist, a fact known to every scholar familiar with the historiography on the Holocaust in Poland; it is the pseudonym of an author – perhaps several authors – who pens lengthy online documents riddled with antisemitic clichés and stereotypes.Footnote157 Mark Paul texts have appeared, predictably, in Glaukopis,Footnote158 as well as on the website of the aforementioned far-right-wing Toronto branch of the Canadian Polish Congress. Some of his texts appear published, such as Neighbours on the Eve of the Holocaust, which bears the imprint of Toronto-based Pefina Press. Short for Polish Educational Foundation in North America, Pefina has no apparent editorial board, peer-review process, or even contact details, and its authors include mostly Mark Paul and Piotrowski.Footnote159 Moreover, unlike actual academic publications, the Canadian Polish Congress changes the text of Neighbours on the Eve of the Holocaust every year or two, adding hundreds of references to each updated edition.Footnote160 Inflating Mark Paul texts with footnotes (1,609 in the most recent version of Neighbours) raises their visibility, because a Google search for other titles – those in the footnotes – leads to his work.

Mark Paul’s work, defended by the nationalist group of editors, epitomizes Holocaust distortion. A short excerpt from Neighbours on the Eve of the Holocaust shows its blatant falsifications. ‘A fairly clear outline emerges of some sordid and shameful aspects of the conduct of Jews vis-à-vis their Polish neighbours under Soviet rule,’ writes Mark Paul.

It is an immensely important story that has never before been told and one that redefines the history of wartime Polish–Jewish relations. There is overwhelming evidence that Jews played an important, at times pivotal role, in arresting hundreds of Polish officers and officials in the aftermath of the September 1939 campaign and in deporting thousands of Poles to the Gulag. Collaboration in the destruction of the Polish state, and in the killing of its officials and military, constituted de facto collaboration with Nazi Germany, with which the Soviet Union shared a common, criminal purpose and agenda in 1939–1945.Footnote161

The author (or authors) repeat a tired antisemitic canard of alleged Jewish complicity with the Soviet regime. What they tend to forget is that, statistically, Polish Jews were the most targeted group among the former Polish citizens deported by the Soviets to Siberia during the 1939–1941 period.Footnote162 Furthermore, the alleged massive scale of Jewish participation in Soviet militias was based on perceptions, rather than facts; in the eyes of Polish observers, the shock at seeing Jews in police uniforms, practically impossible in prewar Poland, created a false impression of a massive scale of the phenomenon.

The discussion of Mark Paul as a source on Wikipedia exemplifies once again the nationalist-leaning editors’ resolve to redefine the very notion of reliable research. As in the case of Kurek and Glaukopis, a handful of Wikipedians asked to have Mark Paul disqualified from Wikipedia. In a ‘Request for Comment,’ a Wikipedia process for solving content disagreements, Icewhiz asked other editors for their thoughts. The editor, K.e.coffman, urged against citing Mark Paul, pointing out that ‘he’s published by the non-peer-reviewed PEFINA Press … a WP:QS [Wikipedia-defined questionable source] publisher,’ adding, ‘Paul does not appear to have credentials as a historian, so I would consider him to be WP:QS author.’Footnote163 Editor François Robere agreed, explaining,

[Mark Paul is] virtually unknown outside of a narrow circle of Polish writers, some contested themselves. His citation count on [Google] Scholar is two … and AFAIK [as far as I know] he never published outside Glaukopis, which is an issue both in its own right as well as because Glaukopis itself is questionable. He presented no conference papers that I’m aware of.Footnote164